Everyone who has heard of ramps, loves ramps! Also known as wild leeks, they are one of the most exciting and abundant foods to greet us in the springtime. The flavor is like an exquisite onion — strong, pungent, and healthy as garlic but surprisingly sweet. Every bit of the plant is a premier wild edible, from the tip of the leaves to the base of the bulb.

Fun fact, the name for the city of Chicago comes down to us from the Algonquian word chicagoua, which means the wild leek, Allium tricoccum. “Chicago” — the stinking place of onions!

It is important to understand the anatomy and life-cycle of Allium tricoccum in order to harvest appropriately. As with many onions, these plants have three basic parts:

1) The roots. These grow from out of the base of the bulb from a “nodule” which is technically an underground stem or rhizome. From this rhizome comes the point of growth, expanding vertically. Onions are bulbs, and each layer of the bulb is technically a modified leaf growing off the underground stem or rhizome. (With ramps in particular it is possible to guess the age of the plant, much like one would with tree rings, by counting the layers in the “nodule” or rhizome.) This root nodule or rhizome, if separated from the bulb that grows above it, will grow a new bulb the following year if kept alive or in the ground.

2) The bulb is the storage-organ of the Allium tricoccum plant; it grows seasonally, waxing and waning in size like the moon. Smallest in winter, largest at the end of spring. If undisturbed, the bulb will increase in overall size through the years until it is mature enough to split and divide, thereby cloning itself into two or more plants.

3) The leaves. They emerge from out of the bulb. Younger plants have one leaf; more mature plants have two leaves. Sunlight is absorbed by the green chlorophyll in the leaves, which feeds and powers the rest of the plant’s structures underground. The leaves may be harvested in a sustainable way. However, keep in mind that while removing the leaves will not kill the plant, it will diminish the plant’s ability to gather and store energy.

The most sustainable way to harvest ramps is to wait until they have finished growing for the season. This will be the period of time leading up to just before the foliage begins turning yellow on the tips, marking the beginning of the dormancy stage which will last until the next spring. (The ramp leaves will continue turning yellow and brown down the stem, wilting away until all of their above ground portions have disappeared.)

At this point in the end of their growing season, the bulbs have attained their largest size for the year, and the roots are strongly bound within the earth. Because there is a weak point between the foliage and the roots at the base of the bulb, by gently pulling and tugging at the plant by its leaves, a crack will be heard. This is the sound of the rhizome separating from below the bulb! As the forager continues pulling the plant out of the ground, they are delighted to find that the roots and rhizome have remained in the ground to grow for another year, but the bulb and leaves are harvested and in hand, ready for eating. This is a win-win situation for both human and plant, and the alternative to destructive digging. Harvesting in such a way can be considered regenerative, or symbiotic.

It is also worth mentioning that the ramps are easier to clean when pulled in such a way; with the rhizome left in the ground, the outer skin of the bulb slides off easily, and with it, most of the dirt or mud. See the picture below…

In 2016, I gathered some snapped-off rhizomes into a pot with good soil, as a test to see how (or if!) they would regenerate. In spring of 2017, I uncovered the roots and was pleasantly surprised to find that around 80% of them had regenerated, and were rooting and growing new bulbs. This is scientific proof that ramps can indeed be harvested regeneratively via the method explained above, carefully leaving the rhizxome and roots in the ground but harvesting the bulb and leaves.

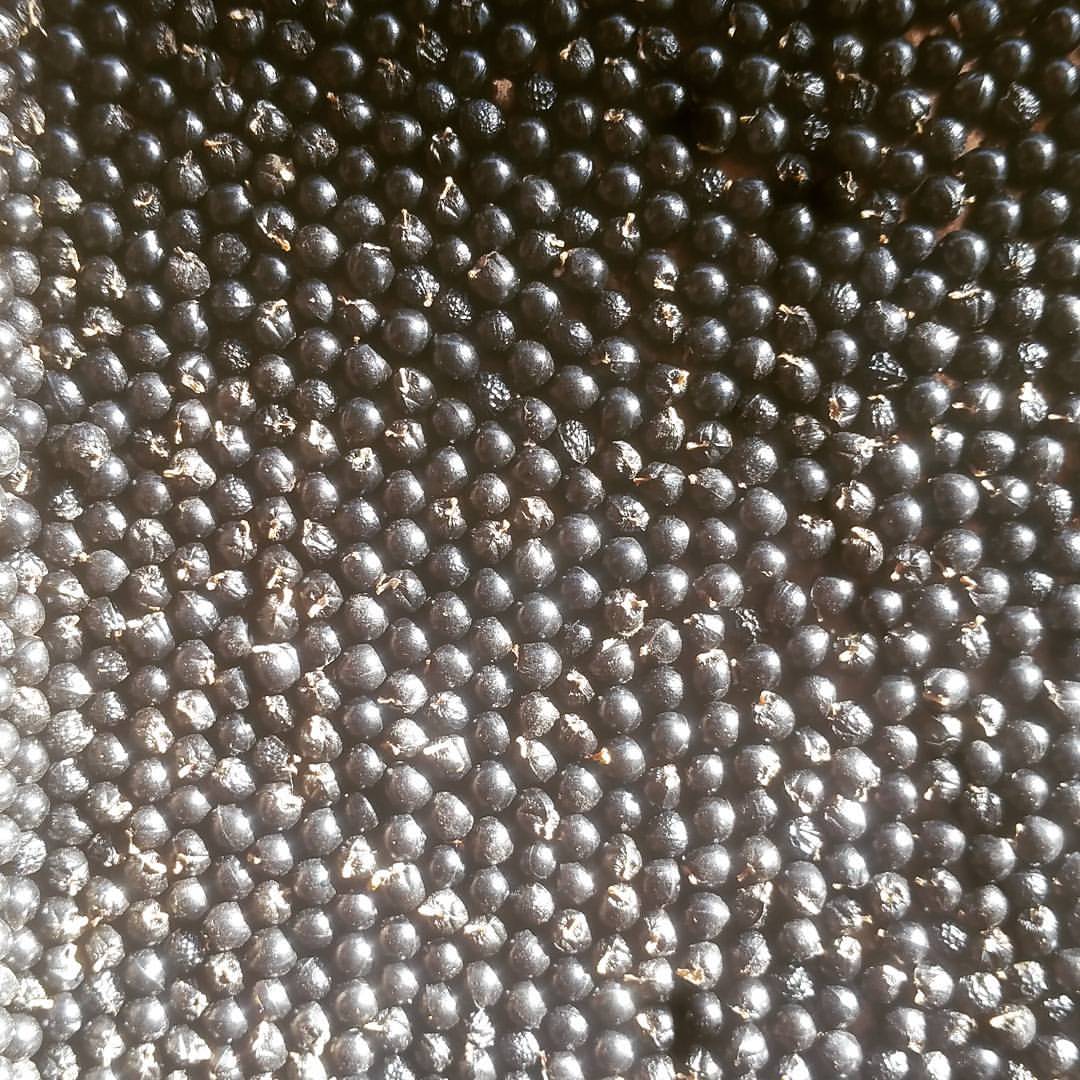

When you are gathering ramps for food in late spring, do not collect any that look like the picture below: it is the beginning of a flower stalk. If left undisturbed, the raceme will continue to grow up 4-10 inches high above the litter of leaves, and at its tip will bloom forth a white, spherical umbel of flowers. These flowers, after pollination, will each go on to develop seeds. These seeds hold within them the future life of the population.

Pictured above is an umbel of Allium tricoccum before the flowers have opened on a late June day in Pennsylvania.

Above is a picture of a ramp flower in bloom. Note how within each flower in the umbel is the ovary, and it is made up of three ovules. This means every individual flower has the potential to develop up to three seeds.

The seeds of Allium tricoccum ripen from mid-September through mid-October.

If the seeds are kept dry and relatively cool in a space out of the light, they will store well for a few years.

Ramps, much like Trilliums, are double-dormant. This means they will not germinate after a single winter cold period, but instead require two winters. If sown in the fall, expect to see the first grass-like seedlings not the next spring, but the following spring after. From germination to flower takes approximately 5 years. Therefore, a ramp plant from seed to flower is a 7 year investment. Consider this before digging up any portion of a patch!

My philosophy is to scatter ramp seed in the same spot for six years. By the time the seventh year arrives, the first seeds sown will flower and soon set their own seeds, and there will already be six generations more lined up on deck. At this point the patch can be considered effectively self-sustaining.

Ramps are an excellent candidate for ecological restoration. They are quite hardy, and will compete well against “invasive” plants such as multiflora rose, japanese honeysuckle vine, and others.

I’ve been seeding new ramp patches since 2014. Here’s are what they looked like this year in 2017:

Thanks Zack & Ulga for a fabulously inspiring day! 💚🌱🌿🍄🌾🌸

Debbie

Hello

I am looking to put Allium Tricoccum bulbs in the ground after the snow clears. I’m in eastern Washington (zone 6) with freezing temps at night (10-25 degrees celsius), often in the 30’s during the day and lots of snow on the ground until April. Since the bulbs can’t yet be planted in the ground can potted bulbs be placed outdoors until such time as they can be planted? Or, can one dig up the snow, plant the bulbs in soil and let the snow cover them? Would it be best to harvest the leaves while still in their pots and transplant the bulbs in the Fall. Will the potted bulbs be able to withstand freezing temps? Will the pots survive being blanketed by snow?

I have a large patch of Viola adunca that has volunteered in my garden under fruit trees and an elderberry. Would this be a good spot to plant Allium Tricoccum?

Larry

Hi Larry,

Allium tricoccum grows natively as far north as zone 3 I believe. It is definitely an abundant plant in even zone 4 Vermont. So hardiness should not be an issue. Your potted bulbs ought to do fine outside, especially if they end up covered in snow (snow is an excellent insulator). In my experience they transplant easily any time of year. I’d say go ahead and put them in the ground after the snows melt. This will allow them to establish as they are actively growing in the spring. They ought to do fine under the shade of your fruit trees. My only concern would be that they remain adequately watered during the dry season months of eastern Washington. You should keep the soil moist periodically through the summer.

Be well,

Zach

excellent info! thanks!!

I live in SW North Dakota, there aren’t any ramps growing here in my area. Every time I go to try & buy seed, they’re sold out! 😕 I was wondering if anyone here would be interested in a seed swap. I have a large shoulder bag plum full of various seeds. From herbs to vegetables to flowers. 😁 if anyone is interested please send me an email at celtgunn@gmail.com

How cold a winter is needed? I’m on the Oregon coast with lots of trillium but not very many winter freezes.

Hi Dave, Trillium don’t necessarily need winter freezes, just seasonal winter cooling temperatures for dormancy. The Oregon coast has a few species of Trillium which ought to do well for you… Trillium albidum, T. ovatum, chloropetalum, kurabayashii, and also Trillium petiolatum and angustipetalum. The southeastern Trillium species should do ok for you too. — Zach

Hi, would it be possible to grow some bulbs in zone 5 in St-Zenon (Lanaudière) in the province of Quebec ? I was searching to find some leaves but unfortunately couldn’t find any in my forest.