At the beginning of March I had the opportunity to join Edwin Bridges, Alex Griffel, and Eric Ungberg down in central Florida for a weekend of botanizing throughout the region’s varied ecosystems, all of which are managed through prescribed fire. Edwin runs his own botanical and ecological consulting business, and his encyclopedic knowledge of the area’s flora is impressive. His work in ecosystematics presents a comprehensive picture of the ecological workings of the region. Alex is a graduate of the University of Central Florida and has worked with The Nature Conservancy’s Tiger Creek Preserve burn crew. Eric Ungberg is with Duke University’s plant lab, and was down in Florida for some of the same reasons I was, such as curiosity and the love of botanizing. All were great people to be around and to learn from.

Along the way we noted several rare, endangered, and endemic species found only in central Florida’s sandhill communities. A few species had even narrower distributions, being found only within the county we were at, Polk county, and neighboring Highlands county.

The first site we looked at was a longleaf pine savanna adjacent to two slash pine plantations on the Avon Park Air Force Range. The savanna with longleaf pine (Pinus palustris) in the canopy had an understory of saw palmetto (Serenoa repens), dwarf live-oak (Quercus minima), wiregrasses (Aristida spp.), bluestem grasses (Andropogon spp.), several forbs, and other grasses and sedges.

The savanna had been burned January 12th, 2017. Edwin and Alex were taking measurements and systematically studying the growth rates and flowering and fruiting times (phenology) of resprouting species in the plot post-fire. The object of their study was to document the effects of fire-seasonality and determine the ideal times for burning.

Central Florida does not experience the four seasons like much of the rest of the continental United States does. Instead, there is a wet season, and a prolonged dry season. The wet season is generally from May-October and is characterized by almost daily afternoon thunderstorms brought about by the warm sea breezes along the coast. During the dry season, from around October until May, cold fronts from the north push away the humidity of the sea breezes, and the result is seven months with little rain. While there may be occasional rain during the dry season, such rains are brief or erratic and pass overhead quickly carried on the fast-moving cold fronts.

Central Florida’s climate during the dry season is exceptionally xeric, or dry. There is not much soil to speak of in central Florida, but there is an abundance of white beach sands. Because sand does not hold onto moisture, even during the summer wet season with its abundance of rain, the landscape of the sandhill communities remains largely arid. It is a different situation, however, in the cypress swamps found in low-lying areas.

Historically, central Florida’s savanna communities have been maintained by fires caused by lightning strikes that ignite dried plant materials during the dry season. Because the dry season lasts October-May, the first lightning strikes would perhaps come immediately prior to the year’s first thunderstorms in late spring. This leaves a narrow window for the fire from a lightning strike to do its job before hard rains come following in the wake of the storm, and this raises some questions. When exactly did the lightning fires usually burn? How extensive was the burning? How regular was the burning? These questions guide our understanding of what is called fire-seasonality.

If fire comes too soon, say in November, it can destroy the developing seeds of the grasses, impairing the landscape’s ability to regenerate post-burn. And if fire comes too late, say in July, it will destroy actively growing grasses, shrubs, and forbs. One component to fire-seasonality is ground moisture levels, and another is the availability of dried fuels on the surface available as incinerants. Burn at the wrong time, and the fire won’t move properly across the landscape in a tidy and efficient way. It may stop constantly and have to be re-ignited, or the fire may fail to ignite certain patches, leaving some areas untouched by flame. Burn at the right time however, and the fire makes a clean sweep across the ground in one effective action and gets the job done.

Studies in fire-seasonality suggest that the ideal time for fire is during the transition between the dry and the wet seasons, usually around April and May when combustible materials are at their highest accumulations, soil moisture and air humidity are at their lowest, and many grasses and forbs are dormant. When the first thunderstorms come in May, there is a brief window in time where the lightning strikes preceding a storm can burn smoothly across the landscape.

Some suggest that anthropogenic fire-management by indigenous peoples may have maintained the savannas more effectively and more regularly until our present era of fire-suppression. This is a point of controversy and I’ll leave the question open. I will only remark further to say that I think the most practical answer is that there has been a combination of both phenomena, the natural lightning strikes being augmented by anthropogenic fires.

What we do know is that lightning strikes have been the force driving the evolution of fire-adapted plant species in central Florida. This is known because the age and antiquity of fire-dependent trees such as the longleaf pine (Pinus palustris) and sand pine (Pinus clausa) precedes human occupation of North America’s southeastern coastal plain.

To landscape managers, an understanding of fire-seasonality is important because it informs the decision of when to do a prescribed burn in an area, and how frequently. Prescribed fire is a form of biomimicry, so it is important that our interactions with the land produce results that reflect or fulfill the trajectory of natural processes.

Florida has many species which have evolved special adaptations to frequent fire. Longleaf pine (Pinus palustris) is perhaps the most famous. Longleaf pine has a range across the southeast, from southern coastal Virginia, to eastern Texas, and down into central Florida. Unfortunately, the remaining longleaf pine forests of today are threatened and occupy only 3% of their former density before the age of European colonization and widespread timbering.

Longleaf pine can live for many years in a low shrubby or grass-like form called the grass stage. The needles come in bundles (or fascicles) of three and can be up to a foot-and-a-half in length. They are especially long when the tree is in the grass stage, because they offer protection to the fuzzy white growing tip shielded in the middle, known as the “candle.” If the growing tip is destroyed by fire, the tree dies. By encircling the candle in bundles of needles, the density and moisture of the longleaf pine’s foliage keeps the candle safe from open flame. Longleaf pine may persist is its grass stage for many years, investing its energy into a strong taproot. Then, when conditions are right, the longleaf pine experiences a grow spurt, and will shoot up rapidly, as much as 6-10 feet in only a couple years. Their spurt takes them to heights just beyond the licking tongues of flame across the ground below, ensuring the safety of the tree’s canopy and growing tips.

Longleaf pines can grow to be well over one-hundred feet tall and they can live for half a millenium. In one early European encounter in the longleaf pine forests of the southeast, it was said that four men hand-in-hand could not wrap around the base of one of these primeval trees. We are left wondering about the magnitude and majesty of these forests before the age of logging.

In central Florida, however, frequent hurricanes during the wet season are enough of a disturbance to mature longleaf pines that few of the trees survive beyond about 150 years in age, and they do not seem to grow to the same towering heights that may be found in coastal areas further north and inland. The prime habitat for towering, impressive forests of longleaf pine would have historically been areas of southern Georgia, Alabama, and South Carolina. Despite the harsher environment of central Florida, the longleaf pine savannas we encountered here had a beauty and order entirely their own.

Sand pine, or scrub pine — Pinus clausa — is another fire-adapted pine of the region. It grows shorter and branchier than its longleaf cousin, Pinus palustris. Sand pine has small cones that remain tightly closed after dropping from the tree, only to open with heat as a response to fire.

In the herbaceous layer, many plants adapt to fire by forming thickened rhizomes, corms, bulbs, or tubers which serve as long-term storage organs. These plants are known as geophytes, and they have adapted to harsh conditions in their environment by becoming dormant under ground until conditions improve. Their starchy, fleshy roots not only ensure survival after fire, but also act as an energy storehouse throughout the long dry season.

Rose rush (Lygodesmia aphylla) is an example of a geophyte. It is a beautiful wildflower that was seen growing in the burned slash pine plantation (maybe surviving from a time earlier than the plantation) and also in the longleaf pine savanna. It is a member of the sunflower family, Asteraceae, and is grouped in the chicory tribe, Cichorieae. Rose rush will look familiar to anyone who has seen the common chicory (Cichorium intybus). Lygodesmia aphylla is a southeastern outlier in a genus that exists primarily in the American southwest.

In the desert southwest, there is ethnobotanical documentation of Lygodesmia usage as food, spice, and medicine. I did not sample any parts of the plant, but these facts should be of interest to anyone interested in a bioregionally appropriate diet or native garden in central Florida.

Many other flowers were starting to come out in force at the burn site, encouragingly. We saw lots of meadow beauty (Rhexia mariana & Rhexia nuttallii), queen’s delight (Stillingia sylvatica), coastal blackroot (Pterocaulon pycnostachyum), blue-eyed grasses (Sisyrinchium nashii), yellow star-grass (Hypoxis juncea), hatpins (Lachnocaulon anceps and Syngonanthus flavidulus), and milkwort (Polygala setacea), among others.

Meadow beauty is an aptly-named attractive plant that blooms in meadows where there is some seasonal moisture. It is in the meadow beauty family, Melastomataceae. We saw Maryland meadow beauty (Rhexia mariana) and also Nuttall’s meadow beauty (Rhexia nuttallii).

By keeping the undergrowth down and maintaining savanna grasslands alongside the pines, fire-management also provides benefit to the growth of orchids, such as pine pink (Bletia purpurea) and bearded grass pink (Calopogon barbatus) which require open meadow, savanna, and other habitats that experience periodic disturbance. As we explored a low-nutrient seepage fen, we saw dozens of Calopogon barbatus orchids. There could have been hundreds, or even thousands throughout the fen. A fen is a low-lying around that frequently floods. They are often marshy and open, like meadows. In the fen we also saw many carnivorous plants: hooded pitcher plants (Sarracenia minor), sundews (Drosera capillaris), and butterwort (Pinguicula caerulea).

Some of the most incredible habitats of the trip were at The Nature Conservancy’s Tiger Creek Preserve. The preserve is located on a geological feature known as the Lake Wales Ridge.

Lakes Wales Ridge is a holdover from a time long ago when ocean levels were over one-hundred feet higher than at present. Lake Wales Ridge was one of Florida’s “ancient islands” which used to exist surrounded by the Atlantic ocean. The islands were long but narrow, and were home to a xeric, maritime community of plants and animals.

During the last glacial maximum, as sea levels dropped, Florida’s ancient islands began to swallow up more land around them and grow, giving shape to the Florida landmass we know today. The ancient floral and faunal communities of the Lake Wales Ridge expanded outward and colonized the new barren, sandy landscape around them. The only remnant of the ancient islands today is a long chain of sandy ridges running down the center of the state. This forms the Lakes Wales Ridge.

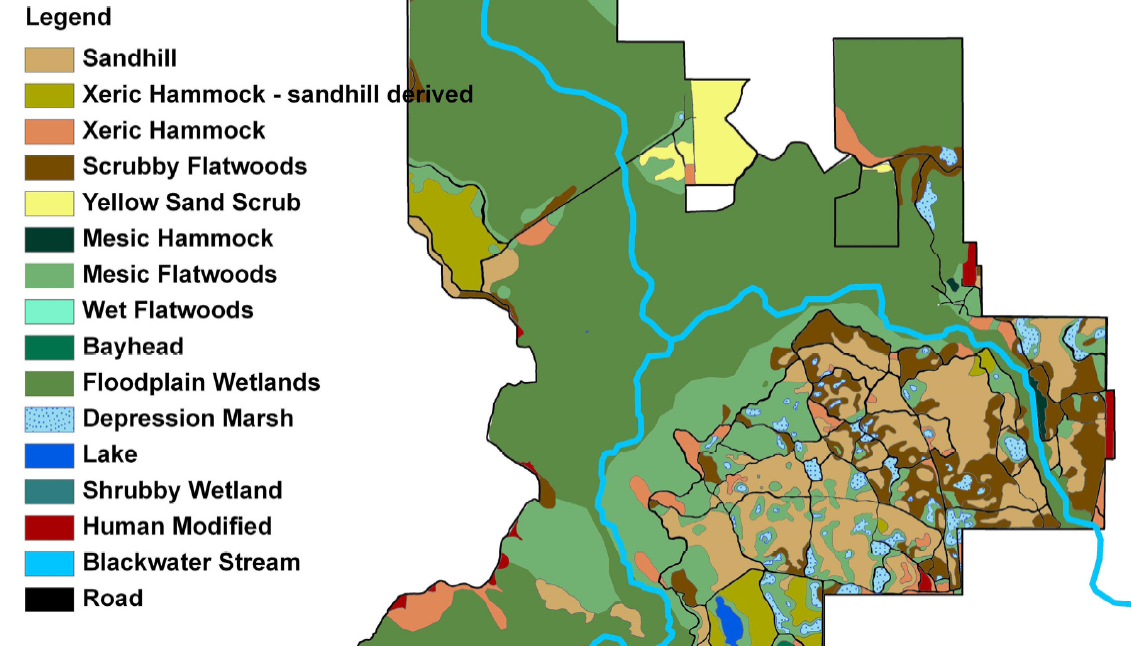

The Tiger Creek Preserve is an incredible place for a variety of reasons. It preserves the natural legacy, history, and ecology of Florida’s ancient islands, but it has also been managed wisely for many years. Prescribed fire has been used here for forty or fifty years. The resulting landscape is one that simply flows — from the wet (or hydric) swamp forests, and the mesic hardwood hammocks, to grassy depression marshes, and out across the xeric sandhill ridges with their longleaf pine savannas and oak scrub. The Tiger Creek Preserve is a place that oozes “natural,” and is a wonderful example of successful management. It has not been chopped up into private property or plantation plots unlike so much of the rest of the state, but has been allowed to develop across all of its ecological gradients, forming smooth, continuous ecotones.

The savannas of the Tiger Creek Preserve had me imagining what the African landscape human beings evolved in may have been like. Reading through The Old Way: A Story of the First People by Elizabeth Marshall Thomas provided mental fodder for comparisons. The savanna of the African Kalahari desert is, like the Florida sandhills, a xeric, sandy environment shaped by fire and sun.

Even with frequent burning, not everywhere is shaped by fire — a few hills or hardwood hammocks naturally sheltered by the Tiger Creek on one side and depression marsh on the other, allowed more mesic species to thrive in the shade of oaks (like Quercus hemisphaerica, Q. nigra, Q. virginiana) and scrub hickory (Carya floridana), such as bigflower pawpaw (Asimina obovata) and red bay (Persea borbonia).

Down lower along the creek were some swampy areas with baldcypress (Taxodium distichum), swamp tupelo (Nyssa biflora), swamp red maple (Acer rubrum var. trilobum), groundnut (Apios americana), spider lily (Hymenocallis latifolia), and marsh plants like spatterdock (Nuphar advena) and bulltongue arrowhead (Sagittaria lancifolia).

I really enjoyed getting to see some of Florida’s native pawpaw species. Being from the mid-Atlantic, the fall pawpaw harvest is always an exciting time. Asimina triloba is the pawpaw most are familiar with. It is a large-fruited, medium-sized tree that grows in rich soils along riverbanks and in the understory of deciduous forests from Georgia to New York and westward through Missouri. It is the northernmost outlier of a largely tropical genus and family. But when you get as far south as Florida, there are eight species of Asimina to be found! I’m happy to have seen two of them, bigflower pawpaw (Asimina obovata), and netted pawpaw (Asimina reticulata).

Here’s the full listing of Florida native pawpaws:

- Bigflower pawpaw – Asimina obovata

- Smallflower pawpaw – Asimina parviflora

- Netted pawpaw – Asimina reticulata

- Four-petaled pawpaw – Asimina tetramera

- Wooly pawpaw – Asimina incana

- Dwarf pawpaw – Asimina pygmaea

- Slimleaf pawpaw – Asimina angustifolia

- …and last, but not least, the common pawpaw – Asimina triloba

We saw some interesting signs of animal life too. Here’s the entrance to a gopher tortoise den! These tortoise can burrow as far as thirty feet, seeking safety, moisture, and cool temperatures deep under the sands.

As well as some native lichens in the Cladoniaceae family…

Finding hog plums (Ximenia americana) was a tasty treat. That’s the funny thing about the a-seasonality of the tropics… one can fine some fruit trees only in flower, and some trees nearby dropping fruit. Fruit is ready, whenever it is ready. In the case of hog plum, we found the shrubby trees in all stages of growth.

Hog plum was quite tasty and I would consider growing it in a climate suitably warm enough for them. According to the USDA, they are hardy down to 20 degrees F, which puts them in zone 9 or warmer. The pit seeds are very lightweight and would probably float in water — this is a possible adaption to seasonal flooding for seed dispersal.

Another interesting native plant was the silk bay, Persea humilis. It’s in the laurel family, Lauraceae, which is known for its aromatic qualities. Other well-known members of the family include sassafras (Sassafras albidum) and California bay laurel (Umbellularia californica). Persea humilis‘ aromatic qualities were no less striking! The undersides of the leaves were also beautiful – hairy and golden, like gilded velvet in the sun. But perhaps most interestingly, this plant is in the same genus as avocado (Persea americana). And its fruit looks like a miniature avocado, with the green flesh and large central seed. It tastes just like one too, though there is hardly anything there to taste! It may be that the avocado was once as small as this is now, and grew larger over time through a domestication process. Perhaps plant breeders could do the same with Persea humilis. It could be interesting to produce a cross of Persea humilis x americana.

Cartrema floridana (syn. Osmanthus megacarpus), scrub wild olive, is another botanical curiosity. In the olive family, Oleaceae, it looks very much like an olive, but is larger, fleshier, and more bitter. It would be a worthwhile experiment to process a collection of these much as one would process kalamata olives and taste the results. First they’d need to be leached of their bitterness for several days in changes of water. Then, they are brined in salt water for a couple weeks until ready.

More than a few of the plants we encountered are narrow endemics to the region and even just to the county we were in. Most are rare and endangered. Their primary threat is suburban development and groves of citrus trees. It was disappointing to see the legacy of so much blatant disregard and wanton degradation of central Florida’s ecology. I would love to see an example of a bioregional and native garden for human food production, to stand as an alternative to the pine plantations, citrus groves, cattle pastures, and suburban lawns which have proven so ecologically destructive. I’ll provide a list of plant leads at the end. For now, here’s more plants:

Continuing our journey through the Tiger Creek Preserve’s sandhill savannas, we came across several more fascinating plants, like these Florida endemic lupines, Lupinus cumulicola. The sky-blue flowers on these beauties graced the distant ridges across the sandhills.

In the scrublands and xeric-scapes, we encountered prickly pear cactuses (Opuntia austrina) and Yucca filamentosa with some frequency.

More plants:

Florida is also a bird watcher’s paradise. I was able to get some good photographs of Anhinga, Limpkin, and Tricolored Heron. Also an alligator, which is kind of like a bird, if you consider that it’s a dinosaur. 😀

One of the most exciting plants to encounter during our excursions was Britton’s beargrass, Nolina brittoniana. It is a member of the Asparagaceae family, as you may notice the similarity to Asparagus officinalis from the photo. Britton’s beargrass is another outlier species from a genus usually found in the desert southwest. There, other Nolina species have documented ethnobotanical usage as foods. The young shoots are edible as a cooked vegetable much like asparagus. The plant is highly fire adapted, and will disappear from the landscape if fires are not frequent enough. Today, populations of Nolina brittoniana are vulnerable to extirpation because of shrinking habitat and fire suppression. It is considered rare in the wild and is a federally-listed endangered species, but fortunately is also being propagated by native plant nurseries.

The following is a listing of plants native to Florida which have value in human habitat food systems. Utilizing these in an integrated ecological garden such as in a permaculture food forestry setup could yield some interesting results.

- Nelumbo lutea — American lotus. Common in Florida wetlands.

- Sagittaria latifolia, S. kurziana, S. lancifolia — Wapato or arrowleaf. Common in Florida wetlands.

- Nuphar advena — Wocus or spatterdock. Common in Florida wetlands.

- Apios americana — Hopniss or groundnut. Common throughout Florida.

- Asimina species — Pawpaw. Eight species native to Florida.

- Licania michauxii — Gopher apple. Common in Florida scrub.

- Quercus species — Q. laurifolia, Q. chapmanii, Q. laevis, Q. inopina, Q. minima, Q. myrtifolia, Q. virginiana, Q. geminata, Q. nigra, etc. Florida has a high diversity of native oak trees.

- Carya floridana — scrub hickory. Has sweet, edible nuts. Common in Florida scrub.

- Ximenia americana — Tallow wood, sea lemon, or hog plum. Common in Florida sandhills and scrub.

- Lygodesmia aphylla — Rose rush. Potential human food usage. Common in Florida savanna.

- Nolina brittoniana — beargrass. If cultivated in a regenerative manner as part of a fire-managed savanna, scrub, or sandhill, could be an enjoyable spring vegetable.

- Prunus geniculata — scrub plum. Common in Florida scrub and sandhills.

- Prunus umbellata — hog plum. Florida scrub.

- Prunus angustifolia — sandhill plum or chickasaw plum. Florida scrub.

- Vaccinium species — V. myrsinites (blueberry), V. stamineum (deerberry), and others. Common throughout Florida.

- Gaylussacia dumosa — dwarf huckleberry. Common throughout Florida.

- Stachys floridana — Florida betony.

- Lilium catesbaei — Pine lily. Corm is a starchy food and is easily vegetatively cloned. Infrequent in Florida savanna.

- Zamia pumila — Coontie or Florida arrowroot. Needs to be leached to remove toxins, but has an ethnobotanical history of use as a native Florida food.

- Cartrema floridana — Wild olive. Potential use as European olive substitute, more research needed.

- Allium canadense — Wild garlic. May be other Allium distributed throughout Florida.

Plus, there are many other plants that will grow well and integrate into Florida ecosystems, but I have limited my list to what is native and most bioregional.

Special thanks goes out to Edwin Bridges for providing suggestions and corrections to this article.

Thank you very much for this incredible survey. The expert narration, information and jaw dropping photographs all add up to a priceless documentation of an endangered ecosystem fighting for it’s life within our nations third most populated state, at twenty two million residents. You have inspired me to track down several of the native shrubs listed in your fine essay above.

Best regards,

Steve Benn

Avon Park, Fl