The Way of the Groundnut

In the pre-colonial history of eastern North America, much of what we know of indigenous lifeways prior to the arrival of Europeans is lost or forgotten. In the wake of this forgetting, a few main myths often get repeated – in particular, the myth of wilderness, and the myth of a dense forest primeval. I’ll deal with these briefly, for building a case against them is not the real focus of this essay, but rather the set-up.

- The Wilderness Myth

Or, the idea that North America was a land largely untouched and uninfluenced in its ecology by the hand of humanity. The wilderness myth was the conceptual foundation stone for the English to refer to their colony at Jamestown as “Virginia,” that is, virgin land.* But contrary to the wilderness myth of European mindset, almost every aspect of the landscapes of the Americas bore the influence of man and human interactions with the ecology. What appeared as wilderness to European eyes, was in fact a cultural landscape. It was managed and tended for countless generations by native peoples. Aspects of indigenous management differed according to bioregion and cultural-linguistic group, but across the continent the principles underlying indigenous management shared more similarities than differences.

The Wilderness Myth invites us to imagine a hard distinction between hunting-gathering and agriculture. It discourages us from recognizing that indigenous peoples could have been horticulturalists without being agriculturalists. It encourages us to think that nomadic hunter-gatherers were aimless wanderers who lived hand-to-mouth, caught between feast and famine.

Not only is the wilderness myth wrong historically and ecologically but it also erases or hides the impact of the native cultures and peoples who preceded those of us of European extraction. At its worst, the wilderness idea is a racist one, because it insists that native peoples were unsophisticated and too primitive to have any effect over their ecology. The myth implies that native peoples were not conservationists, or that they had no land care ethic for good stewardship. This particular aspect of the wilderness myth insinuates that native peoples did not over hunt or cause the extinction of animals like the buffalo, for instance, not because they were judicious or practiced good stewardship, but rather because they couldn’t – human population numbers were supposedly too low to have that kind of impact.

(* It has been brought to my attention that Virginia was named in honor of Queen Elizabeth I, the “Virgin Queen.” While this is a historical fact, the naming of Virginia still carries the rhetorical momentum of the “virgin wilderness” idea. Allusions to a “virgin land” were probably not lost on Walter Raleigh when he named Virginia Brittania in 1584. Throughout Hariot’s 1590 text, “A Briefe and True Relation,” the theme of a “virginal land” was presented repeatedly using illustrations of the native inhabitants in their modesty and virtue, and the land’s resources available for the taking — “Virginia” being so-named, like a virgin bride-to-be of England…)

- The Forest Primeval

A popular folk story says that prior to Columbus, eastern North America was so heavily forested with old growth, virgin timber that a squirrel could leap from branch to branch without touching the ground, all the way from Maine to the Mississippi River.

This myth is actually of more recent construction, e.g. probably emerging sometime in the mid to late 1800s. The first European accounts of America mention the widespread and seemingly ubiquitous practice of Indian burning of grasses and woods. Burning was done to create and maintain meadows, and to give forests an open or park-like quality, with widely-spaced trees, free of fallen sticks and underwood, and shrubs. Open woods nurtured an understory of grasses, providing habitat and forage for animals that the native peoples hunted. The wide spacing of the trees allowed enough sun exposure to grow an abundance of roots and fruits. As colonization unfolded it also made travel easy for European horses and carriages.

Numerous early accounts mention passing through meadows, savannas, and barrens devoid entirely of timber. In old land surveys in the 1700s the phrase “poisoned field” appears, because Europeans didn’t realize that the open savannas they encountered were maintained by human-caused fire; rather, they thought that perhaps no trees grew because the soil was too poor.

Eastern prairies were also mentioned in early accounts, where grasses were as high as a man on horseback and the only trees were found right up along the banks of the rivers where the land was too moist to burn. The whole of the Shenandoah valley, some 1,000 miles square, was said to be a vast prairie. Herbs of bison in the east numbered in the thousands, and there were also countless elk, deer, bears, and wolves. (Hu Maxwell, “The Use and Abuse of Forests by Virginia Indians,” 1910)

The first colonies and European settlements were often built on top of older native settlements or “old fields” – areas previously cleared by Indian burning. This was a logical choice, because the ground was already fit to be plowed. In an 1881 history of Rowan county, North Carolina, historian Jethro Rumple noted that a settler arriving in 1750 found a land “destitute of forests” and “had to haul the logs for his house more than a mile.”

So why do we have this myth? Eastern North America has a humid climate with annual rainfall exceeding 40 inches in most places. As the Europeans occupied former Indian lands, they discontinued the practice of burning the woods and meadows. Within single digit years, “savannas,” “meadows,” and “barrens” of former description became “sapling lands” where thickets of oak and hickory grew up. Within the span of one or two generations after fire suppression, nearly all the areas which had once been prairie or savanna were turned into forests. Today, nearly all undeveloped and unburned land in the eastern United States is forested. When combined with the Wilderness Myth which says that native peoples did not modify their environment, one arrives at the logical conclusion that prior to colonization the land must have all been forested.

I mention each of these myths in order to clear the set, making way for a new scene. Now that they’ve been pushed aside, what do we actually know of eastern North American indigenous lifeways?

It turns out that through some historical research, botanical inferences, and horticultural knowledge, we can reassemble the components of a major indigenous human lifeway in eastern North America. No lifeway may be faithfully recreated from historical fragments, of course, nor translated through a reductionist lens, for that matter, but I am constrained by necessity here to limit myself in this discussion. I share this that it may be an inspiration. And I share this now as a prelude to a more comprehensive piece later.

Let’s follow the trail of the potato vine, Apios americana…

Peapatch Meadows

Early accounts of eastern North America around the time of European colonization – particularly in the piedmont bioregion – make mention of meadows filled with peavines. Peavine is a name that could apply to any vining plant in the pea family, but as an old-timer name it referred to the groundnut or potato bean. In these old accounts that follow, it meant one thing: Apios americana.

The first description of Apios americana from a white man comes from Thomas Harriot in a 1585 expedition documented in “A Briefe and True Report of the New Found Land of Virginia.” Harriot writes of “Openauk, a kind of root of round form, some of the bigness of walnuts, some far greater, which are found in moist & marish grounds growing many together one by another in ropes, or as though they were fastened with a string. Being boiled or sodden they are very good meat.”

Another description of the indigenous food plant comes in 1602 from John Brierton, who learned of “ground nuts as big as egges, as good as Potatoes, and 40 on a string, not two ynches vnder ground.”

In 1771, from the Swedish settlement of Raccoon (now Swedesboro, New Jersey) Peter Kalm in “Travels Into North America; Containing Its Natural History, and A Circumstantial Account of Its Plantations and Agriculture in General” writes:

“The Indians had their little plantations of maize in many places; before the Swedes came into this country, the Indians had no other than their hatchets made of stone; in order to make maize plantations they cut out the trees and prepared the ground in the manner I have before mentioned*. They planted but little maize, for they lived chiefly upon hunting; and throughout the greatest part of summer, their Hopniss or the roots of the Glycine Apios, their Katniss, or the roots of the Sagittaria Sagittifolia, their Taw-ho or the roots of the Arum Virginicum, their Taw-kee or Orontium aquaticum, and whortleberries, were their chief food. They had no horses or other cattle which could be subservient to them in their agriculture, and therefore did all the work with their own hands. After they had reaped the maize, they kept it in holes under ground, during winter; they dug these holes seldom deeper than a fathom, and often not so deep; at the bottom and on the sides they put broad pieces of bark. The Andropogon bicorne, a grass which grows in great plenty here, and which the English call Indian Grass, and the Swedes Wilskt Grass, supplies the want of bark; the ears of maize are then thrown into the hole and covered to a considerable thickness with the same grass, and the whole is again covered by a sufficient quantity of earth: the maize kept extremely well in those holes, and each Indian had several such subterraneous stores, where his corn lay safe, though he travelled far from it. . . .”

Benjamin Hawkins, in a “A Sketch of the Creek County in the years 1798-1799” regarding his travels through Georgia and Alabama, writes:

The country above the falls of Oc-mul-gee and Flint rivers, is less broken than that of the other rivers. These have their sources near each other, on the left side of Chattohoche, in open, flat, land, the soil stiff, the trees post and black oak, all small. The land is generally rich, well watered, and lies well, as a waving country, for cultivation. The growth of timber is oak, hickory, and the short leaf pine; pea-vine on the hill sides and in the bottoms, and a tall, broad leaf, rich grass, on the richest land. The whole is a very desirable country.”

The historian William Henry Foote, writing “Sketches of North Carolina” in 1846, wrote that:

“The county was comparatively new; and it was not yet forty years since the first of those composing the convention had settled in the wilderness. Agriculturists, at a distance from market, and in a fertile country affording in its pea-patches, and cane-brakes, and prairies, plentiful sustenance for their herds, they had abundance of provisions, and little of the sinews of war, money.”

The same historian, writing of the Shenandoah Valley in 1856 in “Sketches of Virginia:”

“A large part of the valley, from the head springs of the Shenandoah to the Potomac, or Maryland line, a distance of about 150 miles, embracing ten counties, was covered with prairies abounding in tall grass, and these, with the scattered forests, were filled with pea vines. Much of the beautiful timber in the valley has grown since the emigrants chose their habitations.”

In an 1881 “History of Rowan County [North Carolina],” Jethro Rumple writes:

“The foregoing quotation presents several points of interest. The first is that the country was not then – one hundred and eighty years ago – clothed with dense forests as we are apt to imagine, but was either open prairie, or dotted here and there with trees, like the parks of the old country. Along the streams, as we gather from other pages of his narrative, there were trees of gigantic height, so high that they could not kill turkeys resting on the upper branches. This agrees with the recollection of the older citizens, and the traditions handed down from their fathers. A venerable citizen, now living in the southwestern part of this county, remembers when the region called Sandy Ridge was destitute of forests, and that his father told him that, when he settled there, about 1750, he had to haul the logs for his house more than a mile. Another honored citizen of Iredell, lately deceased, told the writer that he recollected the time when the highlands between Fourth Creek and Third Creek were open prairies, covered with grass and wild pea-vines, and that the wild deer would mingle with their herds of cattle as they grazed. A stock law in those days would have been very unpopular, however desirable in these days of thicker settlements and extended farms.”

In 1897, J. B. Landrum in “Colonial and Revolutionary History of Upper South Carolina” writes that “it is a fact well authenticated, that in the early history of the upper country there were numerous prairies covered only with the grasses and the pea vine, but which have since been covered with pine, oak, and other growth.” He offers up the following description:

“Up to the breaking out of the revolutionary war, the woodlands in the upper portion of South Carolina were carpeted with grass, and the wild pea vine grew, it is said, as high as a horse’s back, while flowers of every description were seen growing all around. The forests were imposing, the trees were large and stood so wide apart that a deer or buffalo could be seen at a long distance; the grasses and the pea vines occupied the place of the young, scrubby growth of the present day.”

Further west, beyond the Appalachian mountains and into the interior of the continent where were the Great Plains, the same scenes of groundnut meadows were related in similar detail. Along the Missouri River, Lewis & Clark wrote in 1805 that “on those Streams the lands verry fine covered with pea vine & rich wood.” In 1819-20, Major Stephen H. Long spoke of groundnuts in “Account of an Expedition:”

“The woodlands here, as on the whole of the Missouri below, are filled with great numbers of pea vines, which afford an excellent pasturage for horses and cattle. The roots of the Apios tuberosa were much sought after, and eaten by the soldiers, who accompanied us in our ascent.”

Prince Maximilian of Wied described the same scene along the Missouri in 1832:

“. . . On open spots on the ground, the pea vine – a very useful plant – and the lily of the valley [he was probably describing Camassia scilloides] grows everywhere in profusion. The pea vine is a climbing plant, the foliage of which is excellent fodder for cattle and horses, which grow very fat from it. On its root grows a bulb the size of a small walnut with a somewhat violet-colored shell, completely white on the inside, which provides very tasty, nourishing food.”

The botanist Frederick Pursh, traveling on foot in 1805 over 3,000 miles from Maryland to the Carolinas with little more than just a gun and his dog, encountered an abundance of groundnut along the way. Many of the places he walked through had not yet been colonized by Europeans. Following his travels, he wrote “Flora Americae Septentrionalis” in 1814 and therein writes that groundnuts were commonly found in “mountain meadows” from Pennsylvania to the Carolinas. What could he have meant by these “mountain meadows,” if none other than the upland savannas created through Indian burning previously attested by multiple authors?

“Glycine Apios…In hedges and on mountain meadows : Pensylvania to Carolina…Flowers dark-brown, sweet-scented; roots eatable, growing sometimes to an enormously large size.”

To the modern Western mind, it seems unbelievable that so much of the landscape could have been under cultivation of a perennial staple root food. These pea-patches were more than just wild food, they were indigenous gardens.

Cultivation

Archaeological evidence shows that groundnut was consumed as a food by humans at least as far back as the Archaic Period in early American history, 8000-1000 BC. Joseph Harl, in the “Archaic Period of East Central Missouri, on page 377 writes:

“…at the start of the Early Archaic, the prairie grasslands were first invading the interior upland portions of the Salt River [a tributary of the Mississippi in Missouri] drainage basin. The grasslands, however, were not extensive, as forests covered most of the area. Early Archaic sites were found to be small and scattered across the landscape, situated on stream terraces, at the margins of ridgetops, along interior portions of smaller streams, and within the interior uplands. These sites indicated that Early Archaic people resided in small groups, as first suggested by Chapman, utilizing a mobile foraging economic strategy. …”

This passage is of interest before it not only matches the general description given above of “peavine meadows,” but could be taken to suggest that grasslands began invading interior upland portions of the drainage basin because of anthropogenic fire – the actions of indigenous humans. Such a theory is not a stretch, as that is exactly what was the case with the piedmont regions of the southeast until colonization.

Native American burning of the grasses and woods would not have merely been enough alone to encourage groundnuts to colonize upland meadows unaided. Those who find groundnuts in the wild today think of the plant as one of wetlands, bottomlands, and riverways where the soil is always wet and there is enough access to sunlight. I argue that such habitats are something more like a refugia for the species, rather than its originally intended habitat. In the wake of fire suppression and because so much of eastern North America is forested today, Apios americana has few other opportunities to continue its existence outside of sunny riverine floodplains, wetlands, and other bottomlands.

A friend of mine has planted Apios americana in an upland setting, and the vine has proven itself to be quite happy in this context, spreading everywhere the sun shines. The roots grow big and spread about, running aways beneath the soil’s surface, doing a fine job of colonizing the rhizosphere of a meadow.

That Apios americana may actually prefer growing in meadows rather than wetlands in an idea given credence elsewhere. According to Reynolds, Blackmon, et. al., in “Domestication of Apios americana” —

Although apios in its native habitat is found growing on water-logged and acidic soils (Reed and Blackmon 1985), observations under field conditions indicate that apios grows best on well-drained soils. A pH less than 5 or as high as 8 may also be detrimental to growth. Adequate moisture is important, but excess moisture encourages longer rhizomes.

That groundnuts were once intentionally planted by humans, at least in upland areas (those “mountain meadows” and “peavine grasslands”), by way of either seed or root division, stands as self-evident in the weight of all the other circumstantial evidence.

Philip Juras, author of “The Presettlement Piedmont Savanna”, points out:

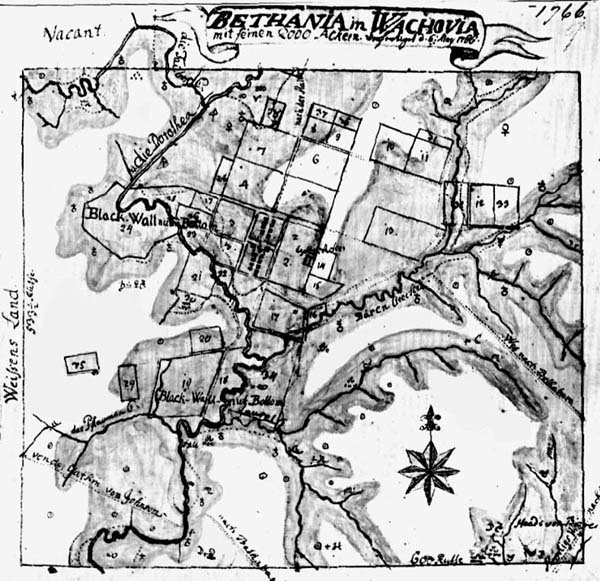

“Though there are no historical maps accurately showing the distribution of savannas in the Piedmont, a demonstration of its pattern in the area of Winston-Salem, North Carolina may potentially exist in a survey map drawn for the Moravian pioneer Community of Bethania in 1766. Shown in Figure 5.2, the white areas between stream drainages could very well represent existing grassland or “prairie” while the shaded areas along creeks may represent forested slopes and bottoms. Support for this idea is illustrated by Keever citing Jethro Rumple’s 1881 Rowan County in which he gives the account of a recently deceased respected citizen, who would have seen the North Carolina “prairie” landscape at the end of the 1700s. The “old timer” says he remembered open prairies on the uplands between creeks covered with grass and wild pea vines where deer mingled with their cattle (Keever 39-40).”

The Moravian map of the Bethania Tract in North Carolina, shown here, is compared to a sketch of Missouri savanna lands. The comparison is striking.

Peter Kalm, writing in 1771:

“Hopniss or Hapniss was the Indian name of a wild plant, which they ate at that time. The Swedes still call it by that name, and it grows in the meadows in a good soil. The roots resemble potatoes, and were boiled by the Indians, who eat them instead of bread. Some of the Swedes at that time likewise ate this root for want of bread. Some of the English still eat them instead of potatoes. Mr. Bartram told me, that the Indians who live farther in the country [e.g., the piedmont] do not only eat these roots, which are equal in goodness to potatoes, but likewise take the pease which ly in the pods of this plant, and prepare them like common pease. Dr. Linnaeus calls the plant Glycine Apios.”

Kalm’s mention of his communication with Bartram is significant here, because it describes a distinction between two forms of Apios americana, which we know to be true today as representing the distributions of the plant’s more southerly diploid form, and its more northerly triploid form. Triploidy results from a mutation that leaves the plant sterile, unable to fertilize its flowers and make beans. Diploid plants, on the other hand, are fully-fertile and produce pods with seeds.

Diploid groundnuts are generally confined to the southern and southeastern portions of the United States. One of the features of Apios americana that I have noticed is that flowering doesn’t occur until after the plant has had a certain length of time to grow and vine out vegetatively. The plant might even by photoperiod sensitive. In the hot and humid climate of the south, this means groundnut could begin leafing out in March and flowering in July, for instance. In a similar but shorter-season climate, such as that surrounding the Chesapeake Bay, groundnut might begin leafing out in April and flowering in August. After flowering, it takes a certain amount of time for the flowers to get pollinated, and then to set and ripen seeds. Collections of seeds I have made in zone 7 were as late as the end of October. In other words, if diploid Apios were growing further north, it wouldn’t have time to ripen its seed before the frosts come.

Triploid forms of Apios americana have been found abundantly throughout the north, as far west as Wyoming and Colorado, and far north as North Dakota (the homeland of Buffalo Bird Woman, who spoke of her people rising up out of the waters of Lake Minnewaukan upon the vining roots of groundnut), and southern Canada. Triploid forms, while sterile, have other values to humans in that they focus more of their energy on the vegetative cycle (being unable to complete the flowering cycle). This means that triploid Apios tubers often grow bigger, faster. And since they don’t set seed they have to be propagated vegetatively, like “seed potatoes.”

At least four genetically distinct triploid variants have been identified. Naturalistic explanations for the widespread distribution of a sterile, non-seeding plant throughout the north invoke theories of rapid colonization following the retreat of the Wisconsin Ice Sheet (Joly & Bruneau, “Evolution of Triploidy in Apios americana…”). I find this explanation fails, because during past glacial maxima, diploid Apios would have been pushed into much more southerly refugia than would allow for the kind of post-glacial colonization suggested by Joly & Bruneau. Analyses such as these often overlook human-plant symbiotic interactions, in an urge whether conscious or unconscious to deny that indigenous peoples could have ever modified their environments enough to shape the evolution of wild plants.

Here’s an alternative hypothesis: humans consciously planted Apios americana as a food root all throughout the eastern half of the continent. They maintained its habitat through fire, to keep open both bottomlands and uplands where it might thrive. As they pushed the plant’s range further north, physiological stressors such as shorter growing seasons with earlier frosts encouraged the development of triploid mutants. Native peoples, recognizing the value of these triploid forms for their larger and faster development, continued the planting of Apios well into the north, where early frosts didn’t matter to a plant that doesn’t seed anyhow.

Native American placenames convey a sense for the significance or abundance of certain natural features, animals, plants, fish, or history. There are place names which make mention of groundnuts. Henry Graham Ashmead, in “Historical Sketch of Chester, on Delaware,” 1883, discusses the Indian name for the city of Chester (near present-day Philadelphia):

“The Indian name of the site of the present City of Chester was Mecoponacka . . . The proper Indian name of Chester creek was Meechoppenackhan, according to Heckewelder, in his ‘Indian Names,’ which signified the large potato stream, ‘or the stream along which large potatoes grow.’ This was corrupted into Macopanachan, Macopanakhan, and finally into Mecopanacha. The Indian tribe which owned the and whereon Chester stands, according to John Hill Martin, was the Okehockings, and were subsequently removed by the order of William Penn, in 1702. . .”

Recall that the Algonquian word for Apios americana as related by Harriot and Brierton was openauk, and was related by Kalm as hopniss, and we see that the Meechoppenackhan above, “large potato stream,” refers to none other than Apios americana. We can break this down another way, perhaps more straightforward: mech “large,” hopen “groundnut,” ack “land or earth or place,” and hanne, “river or stream.”

The site of the present-day city of Chester was once an indigenous root garden!

Another Algonquian root word for groundnut may have been saag. We find this in sagopon, the component of a place name in Long Island, New York (named for the nearby native town of sagaponack, “place of the groundnut”). Explains William Wallace Tooker in 1895 (“The Algonquian Appellatives of the Siouan Tribes of Virginia”):

“The generic name for roots, tubers, or bulbs [in Algonquian] was pen, varying in some dialects to pun, pan, pin, pon, or bun. Therefore the ‘sukapans’ were the tubers of a plant which these barbarous people dug for food and was perhaps their staple product. We, no doubt, find the parallel of ‘Sukapan’ in Sagapon (or Sackapuna), a component of a place name on Long Island, New York, in the term Sagapon’ack, now applied to a post-office and hamlet in the town of Southampton, from the first syllable of which the village of Sag Harbor derives its name. The Micmac (Rand) Segubun, “a groundnut,” is another parallel. One of the towns of the Kuskarawaokes (later known as the Nanticokes), on the eastern shore of the Chesapeake, had the same name.”

In “Uses of Plants by the Indians of the Missouri River Region,” Melvin Randolph Gilmore in 1919 says:

“The Omaha name of Loup River, which is Nu-tan-ke (river where nu abounds). Nu is the Omaha name of [Apios americana].”

Another place name of interest, is possibly that of Topeka, Kansas. According to Ray Schulenberg in the November 1997 journal “Erigenia” (“Annals of Illinois Ethnobotany: Groundnut or Wild Potato”):

“The derivation of the name of Topeka, the capital of Kansas, is relevant to our discussion of groundnut. The question, argued pro and con in Rydford (1968), is whether or not Topeka means something like “groundnut good digging” in one or more Siouan languages. Vogel (1962) has an entry for Topeka, Illinois (named for Topeka, Kansas); he favors the groundnut hypothesis for the origin of the name, and I, after much sifting of evidence, agree.”

Utilizing the same line of thinking, I propose that the city of Saginaw, Michigan is also named after the groundnut. Named for the river which flows through the city, the exact meaning of the Saginaw name has been puzzled over. It is commonly said to mean “place of the Sauk [people],” though it is perhaps more likely to mean “place of the outlet” (from Ojibwe sag, “opening,” “where it overflows”). But as revealed previously, saag/sag has another meaning or aspect, signifying “groundnut.” Thus sag, “groundnut,” + -inaw “place of:” Saginaw, “place of the groundnut,” which grows in “openings” and river outlets (fulfilling also the other aspect of the word’s meaning). The naming of the Sauk people is probably also a reference to both groundnuts and the river’s outlet.

Reference to groundnut is possibly also found in Sagadahoc, the Abenaki name for what is now known as the Kennebec River in Maine.

To the Muskogee Creek, Apios americana was teloki or teloga (signifying the wild peavine), which we find reflected in some place names such as Teloga Creek in Georgia and the Pea River of Alabama which was once known as tellaugue hatche (peavine stream). (“Placenames of Georgia” by John H. Goff, pgs. 61, 467)

The People

Wherever groundnuts are found, there is usually an ethnobotanical record of their naming and use. Hopen, open, openaw, okeepenaw, hopniss, saag, sukapan, sagapon… all are Algonquian dialectical or transliteral variations of the word or reference for groundnut. To the Cherokee, the plant was u-li and its tubers were nu-na. To the Creek is way teloki/teloga. To the Seneca (Onodowa’ga), to’anjergo’o, onono’ta’. In Omaha, nu. Hidatsa, kaksha. Biloxi, Winnebago, and Dakota, respectively, ado, tdo. and mdo.

In the piedmont regions of Virginia and the Carolinas, groundnuts may have been closely associated with eastern Siouan speaking tribes such as the Monacan, Saponi, and Tutelo. When Captain John Smith of Jamestown sailed up the Potomac River, his Algonquian-speaking guides named another tribe living far upstream, who they say came downstream to make war with them every autumn “at the falling of the leaf.” They called these people Monacans, or Monasuckapanoughs, meaning “diggers of groundnuts.” According to James Mooney, the Monacans were one of many Siouan-speaking tribes who had migrated from the Ohio River Valley region and taken up residence throughout the southeastern piedmont regions. They were a socially non-hierarchical, non-agricultural nomadic people who subsided chiefly on roots and hunting, and were considered fierce and independent. William Tooker (1895) writes again, discussing the linguistics and going into detail regarding their name:

“The prefix Mona is undoubtedly the verb signifying ‘to dig,’ occurring in the same primitive form in many Algonquian dialects, from the Cree Moona, in the far north, to the Narragansett Mona, on the east, and is reproduced at the south in the Powhatan Monohacan, ‘sword,’ literally a digging instrument [a digging stick], from ‘to dig,’ prefixed to -hacan, an instrumentive noun suffix used only as a terminal in compound words denotive of things artificial, so designated because so used by the Indians when purchased from the settlers. The same verb figures in other Powhatan cluster words, thus revealing its identity; for instance, in Monascunnemu, ‘to cleanse the ground to fit it for seed,’ making it the equivalent of the Narragansett Monaskunnemun; Delaware Munaskamen, ‘to weede.’ It will be found by analyzing carefully the various synonyms of the term Monacan, or Monanacans, with its English plural as displayed, that it resolves itself into the components of Mona-acka’anough, from Mona, ‘to dig;’ ack, ‘land or earth,’ with its generic plural of -anough, ‘nation or people’ – that is, ‘people who dig the earth’ – the phonetic sounds of which were shortened into Monacans by the English, which may be freely and correctly translated as the ‘diggers or miners.’ The term as such probably designated the whole confederacy collectively. This abbreviation of the sounds of tribal appellatives is characteristic of English notation, as in Mohawks, from Mauqua’uog; Mohegans, from Manhigan-euck; Pequots, from Pequtto’og, and others.”

…

“Farther to the northwest, as laid down on Smith’s map and referred to but once in his history, appears another tribe of the Monacans, under the appellative of the Monasukcapanoughs or Monasickapanoughs. As is evident to all, we have here displayed another name with the same verbal prefix, as in the other cases, signifying to dig. Surely this confederacy well deserved the title bestowed upon them collectively of being the ‘diggers.’ Analysis of this word, as in the previous terms presented, gives us Mona-sukapan’anough, ‘people who dig the sukapan or sickapan.’ [that is, ‘diggers of groundnuts‘].”

Today

In a letter dated 25th September, 1846, Canadian scientist Abraham Gesner urged for the cultivation of groundnut, the root known as saagaaban to the Micmac Indians, as an indigenous substitute for the potato (Solanum tuberosum), which was proving problematic with declining yields:

“I have observed that the saa-gaa-ban is a hardy plant, and withstands the early frosts of autumn. Should it prove to be worthy of cultivation as a substitute for the potato, of which I have little doubt, it will be found to possess many advantages over that root, for it endures the frost and may be allowed to remain in the ground during the winter. It may be planted either in the autumn or spring, and the tops if mowed while they are green will make excellent fodder for cattle, advantages not possessed by the common potato. With such views I earnestly recommend this singular plant to every farmer.”

Although there have been other attempts to farm groundnut, not much has changed since then – the message still falls on deaf ears. Hopefully that will change. But beyond groundnuts usefulness to farmers, I hope to have demonstrated conclusively and persuasively that groundnut is more than just a “wild edible,” a curiosity. It is an important cultural plant, who’s role was a central one among the indigenous people who preceded us. These diverse ancestors – Monacan, Saponi, Lenape, Catawban, Micmac, Hidatsa, Creek, and many more – were united in their love for groundnuts, which they gathered not aimlessly but consciously, investing themselves not along with planting and cultivation but with habitat maintenance.

Modern ecologists and conservationists do a disservice when they fail to recognize or acknowledge the legacy of indigenous peoples on this continent. It is a legacy that is far reaching, from the diversity of species found, to the periodic and regular disturbances such as fire which reordered natural communities from the top down, and to the movements and migrations of plants into new communities. In a time where ecological restoration has become a priority, it is important for us to understand what we are restoring to. It is time for a reappraisal and regeneration of these ancestral practices.

Written by Zach Elfers, February 2019

Great article, thanks. I find the speculation that wetlands today may be a refugia for groundnut rather interesting, and believable as Apios is doing fine in my very well-drained sandy loamy garden in z7a.

What I want to know… where do I purchase starts for the triploid forms?

I have the diploid form, with tubers as small as marbles…

the walnut size (or bigger) would be outstanding, and a valuable addition to the stealth garden!

Dr. Steven Cannon at Texas has many of the best accessions — try email — and there is also the Sam Blackmon collection (I believe he is deceased though). I could also sell you a fee tubers in the spring. — Zach

Hello, will you sell improved diploid Apios americana this year?

Are you able to send a small amount of tubers to europe?

I have been trying to get a improoved diploid strains for several years and either they are not in Europe or no one offers them … or I am unable to find them.

Thanks

Nerad Ladislav

Czech republic

From what I understand, the highest producing selection from Dr. Cannon’s breeding work is named Simon aka 1972. Simon is diploid, producing flowers and pods. If anyone knows of a triploid variety that produces larger yields then Simon, I would love to get my hands on some. I do sell Simon at interwovenpermaculture.com. Happy planting!

Absolutely amazing article! The first time I planted my groundnuts was directly in a field. I thought it was perhaps a mistake, but It was a rushed, last minute planting, and I didn’t have an area under cultivation yet. I was surprised at how great they did. Now I see why.