Following the annual meeting of the NY Nut Grower’s Association on October 17th, Carl Albers told me to check out the bottom of Lake Owasco since I was interested in shellbark hickory. Shellbark hickory is one of America’s very finest of nut trees.

Carl explained that in the bottoms along the inlet to Owasco Lake there were lots of shellbark hickories growing on the west as well as the east side. He described how there was a native settlement there for a long time and that it was archaeologically a very important area. The following morning I made my way over to the Owasco Flats Wildlife Management Area, as the area is known.

There I found the shellbark hickories. A lot of them. Many were large and old trees. They look much like their close relative the shagbark hickory (Carya ovata), but shagbarks have dark brown twigs whereas the twigs of shellbark (Carya laciniosa) are tan-colored, and their twigs are also fatter with larger buds. The shellbark has the largest nuts of any hickory, and by extension any North American nut tree, and is generally annually-bearing. It has leaflets of 7-9 instead of the usual 5 of shagbark. Shellbarks growing in a forested setting can grow very slowly, in some cases adding only about a millimeter of girth per season. What this means practically speaking is that a two foot diameter shellbark hickory could be hundreds of years old.

Along with the old shellbarks there were also old swamp white oaks. Like the outstanding shellbark, the swamp white oak or bicolor oak (Quercus bicolor) is exceptional for having some of the sweetest acorns in eastern North America, often edible raw right out of the shell with little hint of astringency from the tannic acid. The bicolor oak is capable of bearing annually, and can grow nuts that are moderately large in size.

Shellbark hickory

Shellbark hickory leaves

The duo of shellbark hickory and bicolor oak were spaced casually throughout the woodland, occasionally growing near to each other but for the most part they gave each other plenty of space. The space between the older shellbark hickories and bicolor oaks was filled with faster-growing early successional trees including elms, ashes, maples, and some basswood. There was also at least one beech tree. To my eyes it seemed like the forest had at one point been primarily just the shellbark hickory and bicolor oak, and over time the other trees had arrived. Elms, ashes, and maples all have seeds which take the form of a samara. These catch the wind and can disperse over large distances. Whereas the shellbarks and bicolor oaks have large, heavy seeds, making long-distance dispersal difficult or slow, the elms, ashes, and maples are able to rapidly colonize from faraway places.

Bicolor oak

Bicolor oak leaves

The southeastern exposure onto the western shore of the Owasco inlet allowed patchy sunlight to descend beneath the canopy of leaves to the ground below. All over the ground layer were the sprawling vines of groundnut (Apios americana). These climbed over brambles and bushes and brush. Earthbeans or hog peanut (Amphicarpaea bracteata) are also present at Owasco Flats, and in their season they make dense patches of bean vines.

Sprawling vines of groundnut

Apios americana at Owasco Flats

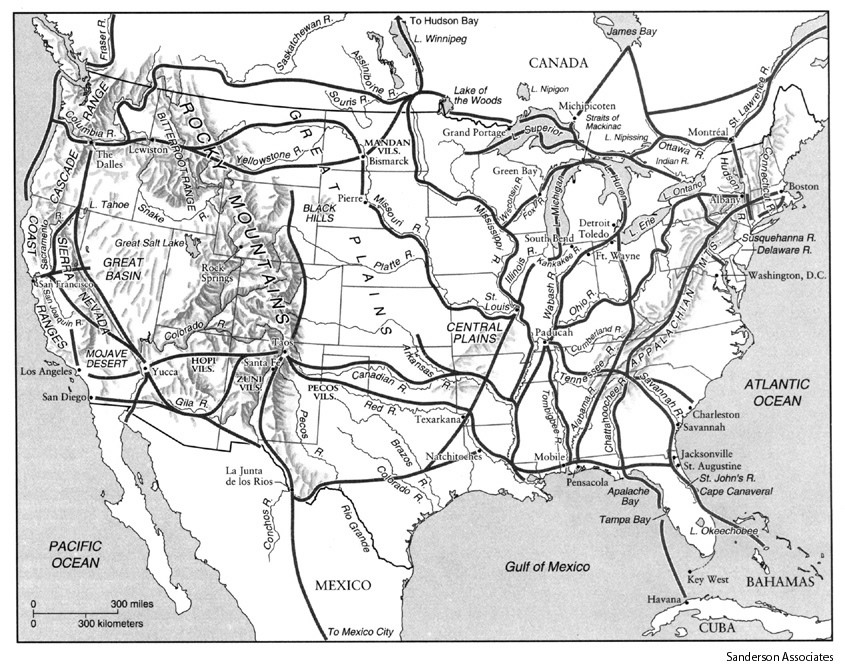

This very place upon Lake Owasco is where archaeologists take the name for the Owasco Culture. This archaeological designation describes the material culture of a pre- or early- Iroquoian people. The assemblage of artifacts these ancestors have left behind are important markers for the western and central NY finger lakes region’s historical timeline. While there is some debate among archaeologists about how clearly Owasco Culture may actually be defined, it is situated geospatially between the Point Peninsula Complex located north of Lake Ontario in Canada and in northern New York, the Clemson Island Culture of Pennsylvania, and the Hopewell tradition extending into New York from out of the Ohio River Valley region of the midwest. Owasco Culture is dated from about 600-1300 AD.

We know that the Owasco Culture grew maize, beans, squash, sunflowers, and tobacco. While the maize, beans, and squash in one form or another may have been present in New York state going back almost 3,000 years, the emergence of the Owasco Culture seems to mark the first time the Three Sisters appear consistently in the archaeological record as an integrated polyculture, starting in about 600 AD. The people of the Owasco Culture are thought of as the first farmers in the northeast, though as we will see later this may be an over-simplification.

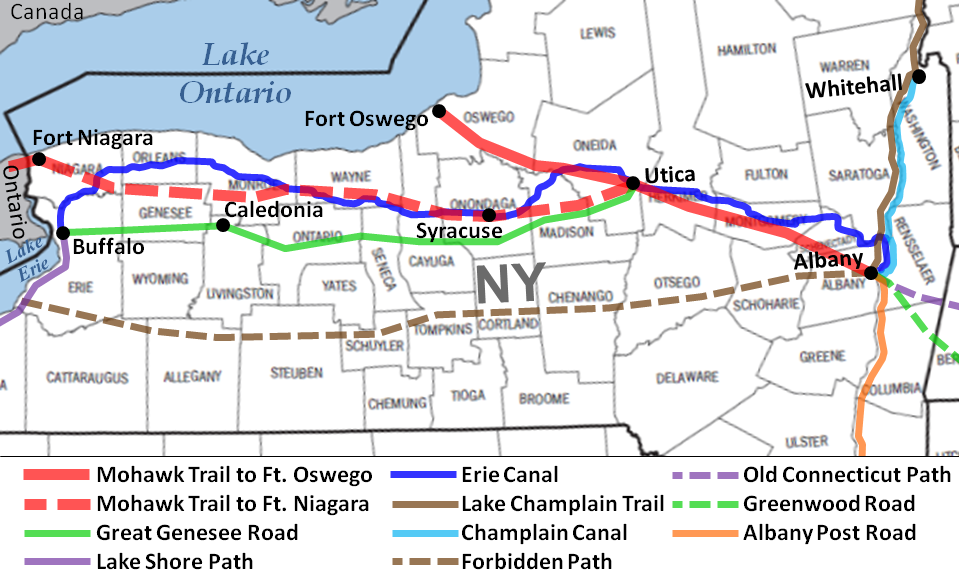

It is believed that the peoples of the Owasco Culture experienced a greater than average level of warfare. They built settlements that were stockaded, and some inhabitants seem to have died violently. Perhaps the increase in violence stemmed from the mixing of different peoples from different cultural traditions. The naming of Lake Owasco is taken from an Iroquoian word meaning “at the crossing,” describing the way in which multiple ancient migration pathways converged in the region that is now central New York.

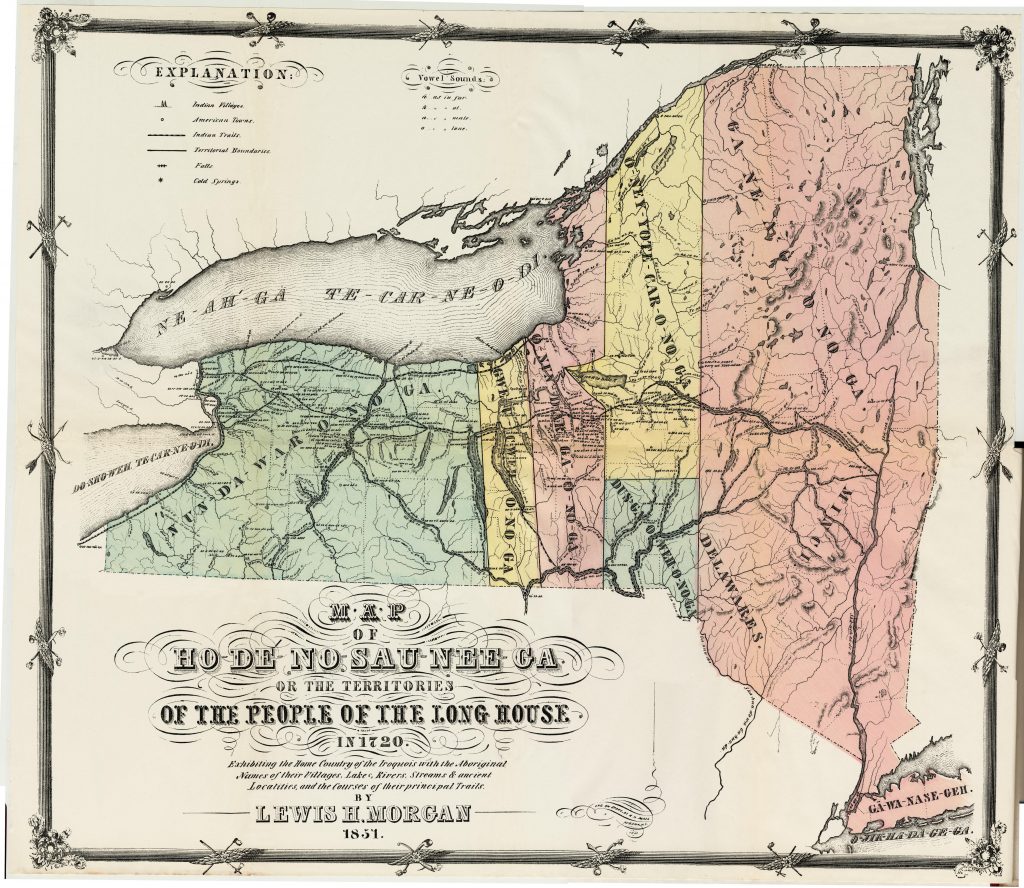

When the Gayanashagowa or Great Laws of Peace of the League of Iroquois Nations were established along the shores of Lake Onondaga a thousand years ago, they brought an end to relentless warfare experienced by the early Iroquoian peoples. It is thought that the people of the Owasco Culture were those peoples. The Great Laws of Peace were revealed by the Great Peacemaker and translated through his spokesman Hiawatha, in the home of the Mother of Nations Jigonhsasee. The treaties served to establish a democratic confederacy known as the Haudenosaunee, or the “people of the longhouse.” To this day it is one of the longest running democratic societies in the world.

Like the longevity of the Haudenosaunee Nations, what is amazing to me is that here beside Lake Owasco, centuries later, the traces of an agroforestry system is still present, seen by the present-day composition of the forest. This is a forest filled with staple foods, from root to crown: groundnut to hickory nut. This existence of this legacy agroforest paints a vivid picture, and also reveals a host of new questions leading us to deeper understanding.

*******

I imagine what this place along the Owasco inlet must have been like back in the days when the native human inhabitants of this land were still burning the woodlands every autumn or early spring. Burning would have kept back the underbrush of fallen branches and brambles. Today the brambles are represented largely by the exotic multiflora rose. Burning would have also eliminated bushes or kept them in small, coppiced forms where the tops are frequently killed only to resprout each season from the living roots. The burning would kill the fire-sensitive saplings of ash, elm, and maple, conserving the wide-open nature of an oak-hickory forest. Not only are shellbark hickory and bicolor oak trees resistant to damage by fire, but their deep taproots allow them to resprout vigorously in case a small, sensitive seedling tree should be accidentally incinerated.

In the wake of firing the woods, in areas of full or patchy sunlight the groundnuts would form into a nearly solid groundcover, like poison ivy but edible, ready to be dug for sustenance at any moment of the year. The earthbeans Amphicarpaea bracteata would also form a solid groundcover but being more tolerant of deep shade, these may be found deeper within the forest. Earthbean, also known as hog peanut, is so-named because it is similar to the South American crop we now know as the peanut Arachis hypogaea. Every autumn the earthbeans form subterranean tubers like pearls along their roots. These are small, seldom larger than a dime, but they make up for their size with their abundance. Gently turning over the soil as the annual vines die back reveals hundreds or thousands of the little lentil or chickpea-sized roots.

Earth bean aerial seeds

Subterranean earthbean tubers gathered in autumn

The groundnuts and the earthbeans fix nitrogen, and the annual fires would decrease nut weevil pests, raise the soil pH toward neutral, and in the process increase the calcium and phosphorous available to the trees. This funnels important macronutrients needed for seed and nut development to the shellbark hickories and bicolor oaks, lending support to their annual-bearing potential and consistency, and positively influencing the size and abundance of the nut harvest.

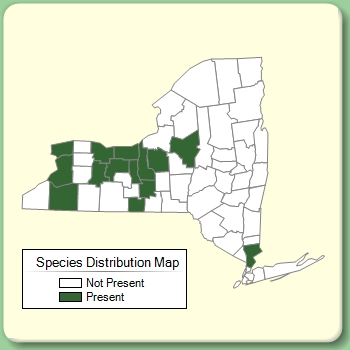

Shellbark hickory is a disjunct species in New York state, meaning that the species is outside of its typical range, which is normally situated over the Ohio River Valley regions and the middle Mississippi River regions of the midwest. But there are scattered incidences east of the Appalachian divide in New York, Connecticut, Pennsylvania, Maryland, North Carolina, and elsewhere. Each one of these scattered disjuncts occupies an area ideal as seasonal camps for hunting, fishing, and gathering. Shellbark hickory is a species that requires a lot of calcium in order to thrive, so it is found in restricted habitats above floodplains and below slopes, where alluvial soils rich in nutrients like calcium get deposited. In many of the disjunct populations, the stands of shellbark are isolated, sometimes hundreds of miles away from the next stand. Several of the populations are associated with known archaeological sites. Here at the inlet for Owasco Lake, it is no different. The shellbarks occupy the nutrient-rich bottomlands nestled amidst what are otherwise steep and nutrient-poor mountain slopes. The fact that shellbark hickory is growing here, at the type site for Owasco Culture, tells a story. Recall how the heavy seeds of shellbark hickory make long-distance dispersal difficult and slow. The unavoidable conclusion is that their seeds were brought here and planted by the human inhabitants of this place. And of course they would have planted them – these trees are regarded as anti-famine trees by indigenous peoples. So says botanist Diana Beresford-Kroeger, whose favorite tree is the shellbark hickory.

Gathering shellbark hickory nuts

Shellbarks developing in July

The groundnuts growing here at the bottom of Owasco Lake are another disjunct. Judging by the lack of flowers or seeds, they seem to be a sterile triploid form of the Apios americana plant. These sterile triploid forms are common in the northeast and upper midwest. What this means in simpler terms is that the plants did not arrive to Lake Owasco as seeds. They arrived already as tubers, and have spread clonally through vegetative means ever since. The tubers grow underground tied together in stoloniferous chains like links of sausage. Each link can be severed and each tuber replanted. In a garden setting, groundnuts can be propagated in a similar way as potatoes, where the “seed potatoes” are actually just replanted potato tubers, not true botanical seeds. Because there are no suitable habitats in the surrounding mountains for this species, the conclusion also seems unavoidable: the indigenous people of Lake Owasco brought these here with them, too.

Welcome to the anthropogenic forest. Overall it is an integrated and beautiful system, and still here centuries later. Cultural landscapes like these are the result of traditional ecological knowledge practiced for generations in place. Cultural forests may be difficult to recognize without the proper context. Indigenous people knew how to build robust, anti-fragile subsistence economies that seemlessly integrated with the broader ecology, and the continuing existence of these forests is testimony to their resiliency.

Like the Haudenosaunee who have maintained their democracy for a thousand years into the present, their nut groves are still here, too. It is only fair that the land be returned to their stewardship.

*******

I want to use the example of Owasco Flats as a centerpiece showcasing what indigenous agroforestry in central New York may have looked like. Just as Owasco defines the pattern of the material culture of the region, it can also define a pattern of floristic assemblies.

Beyond the shellbark hickory, bicolor oak, groundnut, and earthbeans, there are several other plants and trees we can find in the surrounding region presently, and in old flora. Taken individually, the existence of any of these species incidences may not mean so much. But when outliers are spotted, they begin to mean more. Taken as assemblies of species, a story begins to unfold.

American archaeology and anthropology has tended to view native farming systems centered around maize, beans, and squash through the lens of Western farming, which separates cultivated species from their surrounding ecosystems, maintaining annual plants indefinitely through repeated disturbance. Western agricultural practices make it easy to see differences between the domesticated and the wild, and from that perspective it becomes difficult to conceive of a seamless integration of cultivated spaces within the broader ecology. There are few examples of this kind of farming among European settler populations. And we tend to project our own experiences onto those of the past and onto other cultures.

Native peoples, however, do not make such rigid distinctions as between the domestic and the wild. This difference of attitude goes to the heart of what sets Native American and European agriculture apart. Not maintaining a distinction between the cultivated and the wild, it becomes difficult to maintain rigid property boundaries. Whereas European agriculture was settled into fixed fields – a constraint wrought by private property enclosure – Native American agricultural fields were “free ranging” and communally owned. Always changing, shifting, fluid, and mobile. Their’s was a shifting cultivation (or “swiddening”). In practice it was worlds apart from the European agriculture.

If one visits Mesoamerica where the Lakandon and Yucatec Maya still practice their traditional milpa, they would realize how the maize-beans-squash complex represents only the early stages of ecological succession within a system of shifting cultivation incorporating hundreds of species from annual weedy plants all the way up to old growth forest trees. The maize-beans-squash crop complex has dispersed all across North America from Mesoamerica, and is known as the Three Sisters all throughout, from Mexico to Canada. The naming of the Three Sisters rests in story, and story provides context.

In the traditional milpa, the cultivation cycle begins by going into a forest or a thicket and slashing the brush. After being left to dry for a season, the brush is burned off, revealing a barren field. This is slash-and-burn agriculture. Over the ashes are sown the seeds of the Three Sisters, as well as many other annual plants including tobacco, chiles, and amaranth. But milpa workers also sow the seeds of 80-120 other species. The annual multicropping centers around the Three Sisters for only a few seasons at the beginning, and then starts to give way to longer-lived perennial plants as these begin to mature. After the annual multicropping phase, perennial vegetables, small shrubs, and early fruit trees become dominant in the old field for the next few years. (Meanwhile, the slash-and-burn cycle is started anew elsewhere.) Next there is a third phase characterized by tree cover, and the old field transitions into a woodland. In this woodland are many edible fruits and nuts and understory vegetables and herbs. The fourth and final phase is the high forest, characterized by tall canopy trees left to grow for hundreds of years. Eventually, the slash-and-burn cycle will continue again in the same place but that may not happen for decades or centuries.

You can think of the milpa as very long term crop rotation, except that in this case, it isn’t crops that are being rotated, but a representative sampling of the diversity of the whole ecosystem. Slash-and-burn agriculture like that of the milpa has been poorly understood by Westerners. One of the common complaints against it is that it is needlessly destructive, and that after the crops are done the fields are simply abandoned and neglected. But these kinds of practices to the extent that they occur are largely an outgrowth of crop commodification. When the entirety of the ecosystem ceases to be valued at the expense of a handful of cash crops, it is tempting to start cutting corners. That isn’t the traditional milpa. The traditional milpa is full-spectrum subsistence.

- Initiate new cleared area with slash-and-burn

- 80-120 species intentionally planted throughout the cycle:

- Annual multicropping system centered around maize, beans, and squash, 1-4 years

- Perennials, shrubs, and smaller fruit and nut trees, years 4-8

- Fast growing canopy trees (year 7 or 8 onwards)

- Finally mature hardwoods and tall fruit and nut bearing trees, which grow to be decades or centuries in age, until cycle repeats.

- Over a period of decades, a fluid mosaic landscape emerges, rich in ecotonal edges, biodiversity, habitat, and abundance

- Soil is enriched over time with biochar, crop residues, waste, and scraps from kitchen middens

- After centuries and millennia, cultural landscape takes shape

In North America the evidence for slash-and-burn cyclical agriculture is widespread. According to Choctaw elder and scholar Rev. Allen Wright, alabama means “thicket clearers,” a reference to the initiatory stage of slash-and-burn agriculture. The widespread Algonquian place-name saginaw may bear similar meaning, signifying “place of the opening” (where brush was cleared, burned, and gardens grew up). When William Bartram traveled through Creek country in 1792, he observed many kinds of fruit and nut trees growing “in the ancient cultivated fields,” and while his observations come from far outside New York state, in the southeast near Augusta, Georgia, they are nevertheless relevant for the glimpse at full-spectrum cultivation they reveal:

We then passed over large, rich savannas, or natural meadows, wide-spreading cane swamps, and frequently old Indian settlements, now deserted and overgrown with forests [that is, in the later stages of the shifting cultivation cycle]. These are always on or near the banks of rivers, or great swamps, the artificial mounts and terraces elevating them above the surrounding groves. I observed in the ancient cultivated fields: 1. Diospyros [persimmon]; 2. Gleditisia triacanthos [honey locust]; 3. Prunus chicasau [chickasaw plum]; 4. Callicarpa [beauty berry]; 5. Morus rubra [red mulberry]; 6. Juglans exaltata [shellbark hickory]; 7. Juglans nigra [black walnut], which inform us that these trees were cultivated by the ancients on account of their fruit as being wholesome and nourishing food. Though these are natives of the forest, yet they thrive better, and are more fruitful in cultivated plantations, and the fruit is in great estimation with the present generation of Indians, particularly Juglans exaltata, commonly called shell-barked hiccory. The Creeks store up the last in their towns. I have seen above an hundred bushels of these nuts belonging to one family. They pound them to pieces, and then cast them into boiling water, which, after passing through fine strainers, preserves the most oily part of the liquid; this, they call by a name which signifies hiccory milk; it is as sweet and rich as fresh cream, and is an ingredient in most of their cookery, especially homony and corn cakes.

Near native villages on Lake Cuscowilla, Bartram reported:

“the forests were Orange groves, overtopped by grand Magnolias, Palms, Live Oaks, Juglans cinerea [butternut], Morus rubra [red mulberry], Fagus sylvatica [beech], Telia [basswood] and Liquidamber [sweetgum], with various kinds of shrubs and herbaceous plants, particularly Callicarpa [beauty berry], Halesia [silver bells], Sambucus [elderberry] , Zanthoxilon [toothache tree], Ptelea [wafer ash], Rhamnus frangula [buckthorn], Rudbeckia [sochan], Silphium [cup plant], Polymnia [leaf cup], Indigo fera, Sophora, Salvia graviolens [sage], &c.”

In the northeast, we find reference to the cultivation cycle through stories like this tale of the Corn Mother told by the Penobscot:

First Mother said: “Tomorrow at high noon you must do it. After you have killed me, let two of our sons take hold of my hair and drag my body over that empty patch of earth. Let them drag me back and forth, back and forth, over every part of the patch, until all my flesh has been torn from my body.

Afterwards, take my bones, gather them up, and bury them in the middle of this clearing. Then leave that place.” She smiled and said, “Wait seven moons and then come back, and you will find my flesh there, flesh given out of love, and it will nourish and strengthen you forever and ever.”

This story describes the slash-and-burn process, and the First Mother’s bones planted in the clearing can be seen as the seeds of the plants and trees that will grow and nourish the life of the people.

In central and south America, advanced multicropping-agroforestry systems like the milpa practiced for 8,000 years have resulted in large swathes of tropical forest that are anthropogenic in nature rather than the pristine wilderness the European settlers thought it was. North America was no different: this continent was an intimately and intricately tended landscape — a cultural landscape — and it provided so much abundance precisely because humans had nurtured her so faithfully over countless generations. In accordance with the theories of Ester Boserup, indigenous peoples were able to increase the carrying capacity of the land, aided by the ecological tools of shifting cultivation. Thus the Iroquois and other groups spread across the Americas were able to maintain positions of health and affluence without laying waste to the land, despite rises in population.

The milpa, a shifting cultivation system integrating agroforestry, is agriculture as conservation. The milpa is but one member of a family of indigenous cyclical cultivation systems found throughout the forested world. There’s the Tembawang system of the Dayak people of Kalimantan, Indonesia; the Huuhta & Kaski methods of the Forest Finns of Finland and Russia; the Landnam of the Scandinavian Norse; the Jhum cycle of northeastern India and Bangladesh; the Yakihata system of Japan. These integrative, indigenous systems born of deep ecological knowledge share in many features, like an impulse towards reforestation and ecological regeneration — they are the original restoration agriculture.

*******

Lake Owasco takes its name from an Iroquoian word meaning “at the crossing.” The Owasco River inlet was situated along trade routes that wove their way across the landscape for dozens, hundreds, and eventually even thousands of miles. That shellbark hickory, an Ohio River Valley native species, should be present beside Owasco Lake in New York makes perfect sense seen in this light. And it’s not the only one. Trade among native peoples helped to disperse certain plant species across geographical barriers they might not otherwise cross.

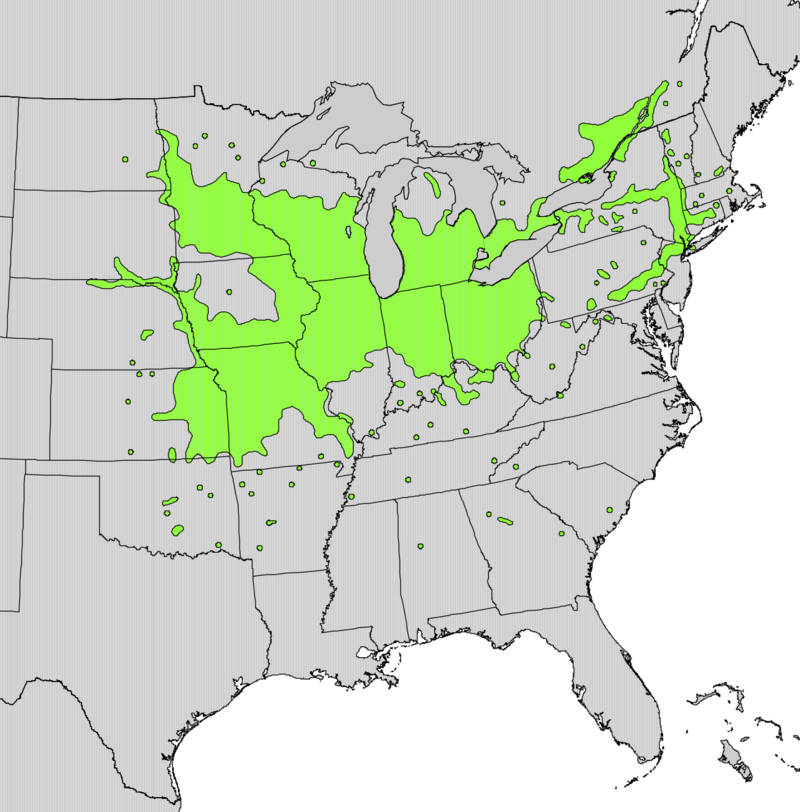

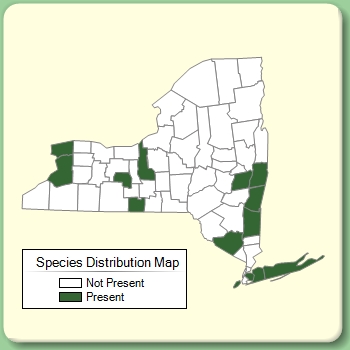

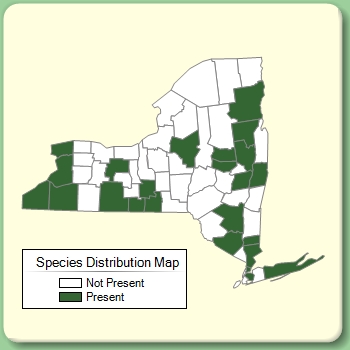

A look through old botanical accounts of the central New York finger lakes region and old flora reveals some interesting finds. In 1807, Frederick Pursh, the eminent German botanist, traveled along the banks of the Onondaga Creek, where on July 12th, he writes: “The road goes chiefly through Oak woods, and crosses a considerable piece of swamp, through which Onondago creek runs close to the road side. I observed plenty of Zanthoxylum fraxinifol [now Zanthoxylum americanum — the toothache tree].” Toothache tree or prickly ash as she is also known, is a relative of sichuan pepper, and may be used as an herbal remedy for toothache and as a circulatory tonic and general stimulant. Zanthoxylum has a rich ethnobotanical history across the eastern half of North America, and taking a look at this plant’s distribution reveals an interesting picture:

It’s hard to look at this map and understand clearly what is going on with all the outlying incidences. Toothache tree has spreading roots that sucker and so is able to form dense colonies. So it can be an aggressive, even obnoxious plant. Are those scattered dots the results of seeds deposited in bird droppings – and if so, why wouldn’t their be a more unbroken distribution? Or are all those dots holdouts from a time the species was more evenly and broadly distributed – but if so, why does the species thrive as well as it does in the hyper-agricultural midwest? Or, could the dots represent areas of native settlement? William Bartram did include this species in a 1792 listing of plants growing beside a native settlement near Cuscawilla Lake in Georgia. I may be out on a limb here – but there are other, more compelling cases yet to come.

Two weeks later, on July 30th, 1807, Pursh was traveling in the area near present-day Syracuse, where the Seneca and Oneida Rivers merge to become the Oswego River, and he writes: “After crossing Oneida River or as they call it Onondaga river which I think very wrongly. I found plants of Anona triloba [Asimina triloba — pawpaw], the first I see all season.”

Pawpaw fruit

So we can add pawpaw to our Owasco agroforestry list! Today pawpaw is extirpated from this region of the finger lakes. Pawpaw is the northernmost member of the tropical custard-apple family, and makes large fall-ripening fruits rich in fats, kind of like avocado. But unlike avocado, these have a unique, creamy, sweet flavor that is hard to describe, but at times reminiscent of banana, mango, or coconut.

Pursh then adds, “Crataegus Crus-galli is very frequent here, & varies in the shape of its leaves most wonderfully.” Crataegus crus-galli, or cockspur hawthorn, is a species with high edible/medicinal value, which just like shellbark hickory, pawpaw, and toothache tree, is also a disjunct – being located outside of its main, traditional range. Hawthorns make a fruit in the form of a pome – they are distantly related to apples, both sharing kinship through the rose family – and the cockspur hawthorn’s fruits become very palatable and sweet after bletting (that is, after experiencing a few freezes).

In L. Leonora Goodrich’s 1912 flora of Onondaga county, we find more fascinating information:

QUAMASIA—Raf. 1818. (Camassia—Lindl, 1832.) Q. HYACINTHINA—Raf, 1836. Wild Hyacinth. Very rare. Banks of creeks etc. Onon. Creek, June, 1900.

Quamasia hyacinthina is now known as Camassia scilloides or eastern camas. Camas, in the finger lakes of central New York!? This is an important cultural plant for native groups of the Pacific Northwest, but the genus has a wide distribution across North America. The large bulbs may be eaten raw and are gummy and sweet, but were usually pit-roasted, which converts the inulin starches into more easily digestible fructose. After roasting, they can be dried and stored, or ground into flour and baked. In my research of this species and from observations in the field, I have concluded that all incidences of camas east of the Appalachian divide are the result of indigenous plantings.

Camas

Raw bulbs

Roasted camas bulbs

We also find in Onondaga county giant solomon’s seal (Polygonatum commutatum): “Rare. Open fields, banks of streams, etc.” This is a species whose shoots make an excellent spring-time vegetable much like asparagus, whose roots serve as a staple starch, and whose flowers and berries are sweet to eat. Solomon’s seal species are known all across the Northern Hemisphere as powerful medicinal plants, as well.

And then we also find thicket bean (Phaseolus polystachios), a relative of lima bean cultivated for the edible beans and pods. This one, Goodrich reports, is rare, growing on “waste grounds, thickets, etc.” Phaseolus polystachios no longer grows in the region, long ago extirpated.

Bicolor oak acorns

Bur oak acorns

Goodrich writes of observing bur oak (Quercus macrocarpa) growing along Phoenix road, which is the same place where she describes shellbark hickory and Kentucky coffeetree (Gymnocladus dioica) growing. This bur oak – shellbark hickory association is not novel, but a repeating theme throughout the overlapping range of these two species. And like our bicolor oak – shellbark hickory duo from Owasco Flats, the bur oak fulfills a similar niche as the bicolor oak, (as well as the chinquapin oak) thus they can be considered interchangeable both culturally and ecologically. The Kentucky coffeetree, a nitrogen-fixing leguminous tree, bears large bean pods with edible seeds. The Kentucky coffeetree fulfills a similar niche as the honey locust (Gleditsia triacanthos), which Goodrich also reports, although rare:

GLEDITSIA—Lam., 1783. G. TRIACANTHOS—Lin., 1753. Honey Locust. Acacia. Rare, except in cultivation. Calthrop Woods, May, 1890.

Like the Kentucky coffeetree, the honey locust bears large bean pods with edible seeds as well as an amber-colored sweet flesh inside the pods that is rich in sugar and very sweet to the taste. Honey locust pods, which sometimes contain up to 38% sugar by weight, is reminiscent of tamarind, and could be considered culturally analogous. An association between honey locust populations and native settlements has been noted before. Both the Kentucky coffeetree and the honey locust fulfill similar niches culturally and ecologically, and so they may be considered interchangeable. As nitrogen-fixing trees, they play important supporting roles to the other trees in the forest. The polycultural trio of oak, hickory, and bean tree might be seen as playing a role similar to that of the Three Sisters. To use the language of permaculture, this is a guild.

Other plants of interest reported by Goodrich in her flora include the sunroots Helianthus tuberosus as well as H. strumosus, the American hazelnut (Corylus americana) which grows “rare” in “open woods,” and the wild red or American plum (Prunus americana) growing in thickets, though “seldom found now.” She reports that American chestnut (Castanea dentata) is “Somewhat localized. Several in northern and southern parts of [Onondaga] county. Rare elsewhere.” She also reports Indian paintbrush (Castilleja coccinea) as occurring in meadows on the Onondaga Reservation, May 27th, 1897. This last incidence is of note because Indian paintbrush is an indicator for high-quality fire-managed meadows, which in central New York state, due to biogeographic factors, cannot be taken as natural but only as anthropogenic.

Let’s turn now to “The flora of the upper Susquehanna and its tributaries” by Willard Nelson Clute, published 1898. Here we find more plants that fit the anthropogenic pattern:

E. bulbosa (Michx.) Nutt. Harbinger-of-Spring. Pepper-and-Salt. Plentiful on first island north of Noyes’ island —the only station, Millspaugh.

Noyes’ island is now the area of Binghamton, New York. Located exactly, as a matter of fact, across from Otsiningo, a native village found on the western bank of the Chenango River, near where she joins with the Susquehanna. Otsiningo and Chenango are two different Anglicized forms of an Oneida word which might mean “bull thistle.” Unfortunately, due to urban development, Noyes’ island no longer exists – the small channel which once separated it from the mainland has long since been filled in, and then the whole area paved over. Yet Otsiningo was a place of importance. During colonial times, this was the Southern Door of the symbolic Iroquois longhouse, kept by the Cayuga, and serving as a welcome station to many indigenous refugee groups fleeing the southern colonies and traveling north, including the Nanticoke, Conoy, Shawnee, Saponi, Tutelo, Tuscarora, and the Mahicans. It was also occupied by Onondaga and Oneida peoples.

Harbinger-of-spring on Noyes island in Broome county, New York, is way out of place from where this species “should” be. Like shellbark hickory, bur oak, Kentucky coffeetree, and others, harbinger-of-spring is native to the Ohio River Valley and Mississippi regions of the midwest. Like groundnut or camas, harbinger-of-spring is an edible root food, eaten raw or cooked. The tubers are small, about the size of marbles sometimes growing the size of ping pong balls, but the plant makes colonies which can cover the ground densely. Harbinger-of-spring is named for being one of the earliest, in many cases the first, wildflowers to bloom after the retreat of winter.

Willard Nelson Clute also noted incidences of shellbark hickory (Hicoria sulcata – now known as Carya laciniosa) “near Waverly” New York. I believe these shellbark trees may still be there, extending down into Pennsylvania somewhat, along the Tioga River. Clute also mentions honey locust or “three-thorned acacia” (Gleditsia triacanthos) as common in Susquehanna and Broome counties. However, many of these were planted by settler-colonists as hedges, which muddies the picture of a native American agroforestry.

Clute also mentions groundnut:

A. Apios (L.) .. Ground-nut. Wild Bean. Tuberous Wisteria. Not uncommon throughout. Found on river banks and in other damp situations, climbing over the surrounding plants. Flowers in dense racemes, pink-brown in color, very fragrant. Edible tubers are borne on underground shoots. Although provided with excellent means for cross-fertilization, this plant seldom sets seed, and spreads mainly by its subterranean runners. Frequently cultivated for shade. Aug.

*******

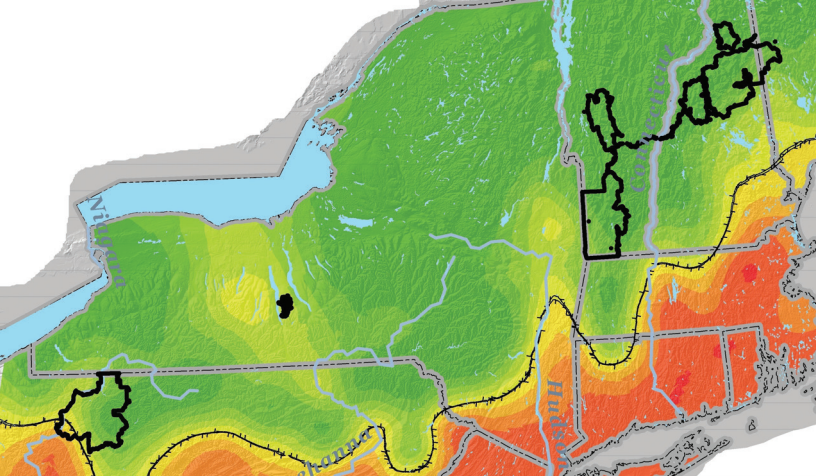

There’s another vector to consider in this discussion, and it is the role of frequent small fires on the landscape. Because of climatic and biogeographical factors, wild fire is exceedingy rare in the state of New York. Instead, it’s existence is an anthropogenic feature that has shaped and remade the landscape of the northeast. The US Forest Service released a good survey in “Mapping Pyrophilic Percentages across the Northeastern United States using Witness Trees, with Focus on Four National Forests.” They turned their survey into a map revealing the pre-colonial fire history of the northeast:

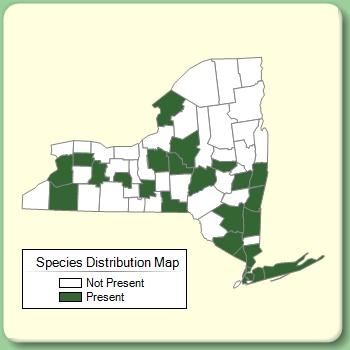

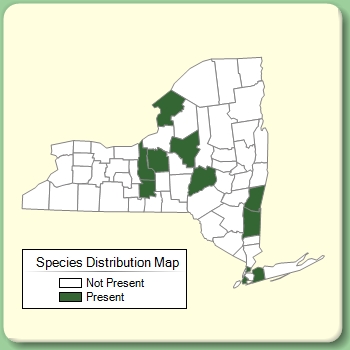

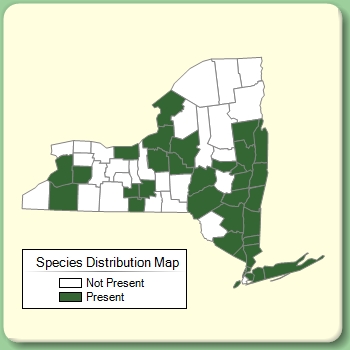

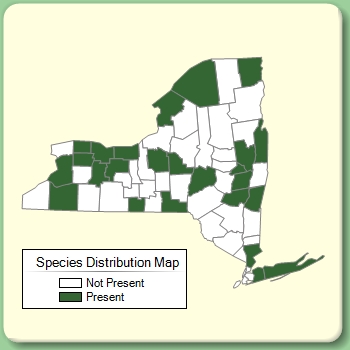

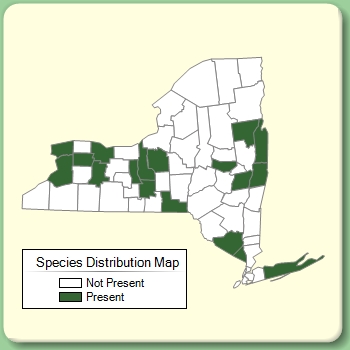

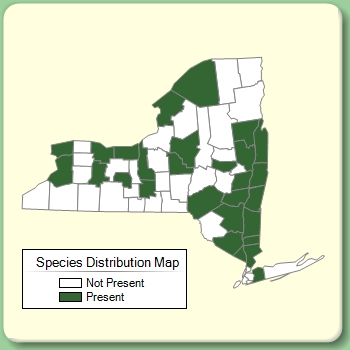

By cross-referencing this map with the distributions of some of our “agroforesty species of interest,” a very clear pattern emerges. Areas with more fire history are more likely to contain these species.

Cue thumbnails…

Carya laciniosa

Crataegus crus-galli

Gleditsia triacanthos

Gymnocladus dioicus

Polygonatum commutatum

Prunus americana

Quercus macrocarpa

Quercus muehlenbergii

Zanthoxylum americanum

*******

At this point, we have assembled an Owasco agroforestry flora complex:

- shellbark hickory

- bur oak, bicolor oak (should add chinquapin oak to list…)

- honey locust

- Kentucky coffee tree

- pawpaw

- toothache tree

- cockspur hawthorn

- groundnut

- eastern camas

- harbinger-of-spring

- giant solomon’s seal

- American hazelnut

- thicket bean

- American plum

- earthbean

- etc.

I’m not suggesting that the presence of all of these plants in central and western New York is exclusively the result of human activities, but that may be true in the case of some of these. What I am suggesting though, with circumstantial evidence, is that these are some of the plants which indigenous peoples cultivated. There are other plants I would add to this list, which I have not covered here in detail. Here are some examples:

- Shagbark hickory (Carya ovata)

- chestnut (Castanea dentata)

- black walnut (Juglans nigra)

- butternut (Juglans cinerea)

- basswood (Tilia americana)

- sumac (Rhus spp.)

- red-osier dogwood (Cornus sericea)

- serviceberry (Amelanchier spp.)

- Viburnum spp.

- currants (Ribes spp.)

- raspberries (Rubus spp.)

- blueberries (Vaccinium spp.)

- strawberries (Fragaria spp.)

- elderberry (Sambucus canadensis)

- ramps (Allium tricoccum)

- etc.,

Because these species are so common, it is harder to implicate them as part of indigenous cultivation and settlement patterns. With a few exceptions – In the case of shagbark, H. Bernard noted in 1980 that their distribution in Quebec, Canada, was “exactly the same as the Iroquois territorial supremacy at the time of the first settlement.” (Bernard, H. 1980. The nut trees of Quebec native and introduced. Ann. Rep. Northern Nut Growers Assoc. 71:21-25. ) There is also a direct account of Iroquois cultivation of American ginseng in 1716, when a French Jesuit “discovered” ginseng after it was introduced to him by some Iroquois. (He observed them gathering the plants by digging the roots when the seeds were ripe, and then scattering the seeds around the hole where they had dug.) Other plants with a probable history of indigenous cultivation include sweet grass (Hierochloe odorata) and wapato (Sagittaria latifolia). The evidence for the history of cultivation of these species in specific locations can probably be found, given enough effort.

Indigenous peoples were in possession of deep ecological knowledge passed down culturally through story, ritual, and tradition. Through ongoing symbiotic interactions with the plant beings around them, over time species increased in abundance. With the advent of integrated, ecological shifting cultivation systems, indigenous peoples were able to transform the landscape like never before.

The existence of cultivated quinoa-like chenopods in Ontario 3,000 years ago is evidence that an integrated shifting cultivation system existed already in the region of western New York before the Three Sisters cultural complex became dominant. Before the Three Sisters, indigenous people in the northeast may have been cultivating the seed crops chenopod (Chenopodium spp.), erect knotweed (Polygonum erectum), and sumpweed (Iva annua) as annual staple grains, during the initial stages of a cycle that probably included agroforestry in the later stages. If you would like to read more about these the work by Natalie Mueller on the “Lost Crops” is worth checking out.

However or whenever the cycle of shifting cultivation came to be in New York, by at least 1,500 years ago it was there. Some of the results can still be seen today, an example of the robust, anti-fragile subsistence systems practiced by indigenous Iroquoian peoples. If the indigenous cultural landscape could be seen four hundred years ago from a bird’s eye view, it would be a shifting mosaic of ecosystems fluidly melding one into the other, and incorporating the full spectrum of diversity of species and habitat types.

*******

The most vivid description of the Cultural Forests of Eastern North America I have encountered so far comes from an early pioneer from the state of Michigan, 1884. What he tells is a sobering testimony to what has been lost, but if we begin to remember, we can let it be so again:

“In the forest we found the whole family of oaks, of the Michigan family, some twelve different kinds, and among them the burr oak, bearing an acorn good to eat, and on which hogs would fatten. In the timbered lands were the new trees called the whitewood [basswood?], of which the best timber for building was made; and the black walnut, more valuable than cherry for cabinet work. It also bore a large and very rich nut, and with it were the whole family of the hickories, all bearing good eatable nuts. Besides these were the butternut, the beechnut, and the hazelnut, all bearing an abundance of their fruit. Throughout the woods we saw the grape-vine hanging from the trees laden with its fruit. We saw vast thickets and long rifts of blackberry bushes lately burdened with their tempting berries. And we were told that the woods and hillsides and openings, in their season were fairly red with the largest and most delicious strawberries, while the wild plum grew along the small streams, the huckleberry and the cranberry on the marshes, and the aromatic sassafras was found throughout the woods. The annual fires burnt up the underwood, decayed trees, vegetation, and debris, in the oak openings, leaving them clear of obstructions. You could see through the trees in any direction, save where the irregularity of the surface intervened, for miles around you, and you could walk, ride on horse-back, or drive in a wagon wherever you pleased in these woods, as freely as you could in a neat and beautiful park.”

“Pioneer Annals” by A. D. P. Van Buren, in “Report of the Pioneer Society of the State of Michigan”, Volume 5, 1884, pg. 250.

*******

Weaving It All Together

Using our provisional flora of Owasco agroforestry, we might begin to imagine how they may have been incorporated into an integratedm shifting cultivation cycle.

We might group these assemblies of flora into sections representing the different phases of ecological succession:

- The garden or vegetable phase, characterized by Three Sisters maize-beans-squash multicropping/intercropping, also including sunflowers, tobacco, and possibly other plants like chenopods, knotweed, or sumpweed. Located primarily on the arable lands in valleys and floodplains.

- The old field phase characterized by hazelnut, pawpaw, plum, hawthorn, serviceberry, and including species like toothache tree, sumac, viburnum, raspberries, blackberries, highbush blueberry, elderberry, strawberry, groundnut, earthbean, thicket bean, etc, and grasses. When left untended these old fields may rapidly turn into thickets, but eventually will give way to closed-canopy forest.

- The mixed woodland phase, characterized by oaks (bur oak, bicolor oak, and more), hickories (shellbark, shagbark, and more), walnuts (black walnut, butternut), American chestnuts, honey locust, Kentucky coffeetree, basswood, etc. (I would add American persimmon to this list but I can find no record of it past or present in this study region of western and central New York.) Forest trees are becoming established, but the canopy has not closed. Reduced light to the forest floor and changing trophic relationships with animals gradually result in the retreat of old field / thicket species, and the advance of forest herbs and roots like harbinger-of-spring, American ginseng, eastern camas, solomon’s seal, ramps, and the host of spring ephemerals.

- The forest phase, characterized by closed-canopy tree cover and stable species representation. Mostly indistinguishable from “wild” forest – you’d have to look closely or find an over-abundance of cultural plants to tell the difference.

Additionally, we might group some flora assemblies into habitat types outside of or parallel to the phases of the shifting cultivation cycle:

- A savanna phase characterized by widely-spaced fire-managed oak-hickory associates (shellbark, shagbark, bicolor oak, bur oak) interspersed with nitrogen-fixing tree crops like honey locust or kentucky coffeetree. May include maples, elms, chestnuts, basswood, etc. The understory could be comprised of grasses, groundnut, camas, giant solomon’s seal, harbinger-of-spring, strawberry, currant, and others. This phase is very similar to the mixed woodland phase (#3), but is maintained in a more open state through frequent firings, OR may exist outside the alluvial areas away from places that come under cyclical cultivation. These savannas might be located along the gentler slopes above the valleys, for instance.

- A steady, or final phase, defined by its long-term consistency and/or unsuitability for other purposes. This phase could apply to areas with semi-aquatic root gardens (wapato, etc.) or to steep, non-arable places, or to wet fens or bogs, or nutrient-poor areas where succession creeps very slowly, such as sand dunes, shale barrens, etc. Such places may contain any number of different species including oaks, chestnuts, cranberries, strawberries, pines, hemlock, birches, maples, blueberry heath, etc. These areas might be characterized by a relational quality of “low-level tending,” rather than by the particulars of a habitat type.

The power of any theory is it’s ability to make predictions. These serve to clarify our understanding of the world. This theory of an Owasco Agroforestry Complex makes some clear predictions, which may turn out true, or false. Only time will tell.

Meanwhile! A different world is possible. This essay is dedicated to all the ancestors indigenous and otherwise who have remembered the beauty in the world.

And importantly, it takes imagination…

Awesome article! I appreciate that you are drawing from a lot of accounts and sources to weave the story together.

Hi Zack – very interesting article, which relates quite a bit to a workshop session I am coordinating (and speaking at) for a conference in March. (I will paste a description to the bottom of this message).

In the meantime – perhaps I missed it, but didn’t see anything in this article about the taste of Shellbark Hickories, or how easy they shell out, as compared to Shagbarks (my #1 favorite wild edible species). BTW – your article helped clarify why I have not encountered Shellbarks where I live (in low-pH soil eastern New England).

OK, here’s that workshop description:

Edible, Medicinal and Other Culturally-Significant Plants: Recognizing, Respecting, and Restoring Traditional Uses

Before European colonization and settlement began four centuries ago, the indigenous inhabitants of the region now known as New England held its lands and waters, and the plants and animals living there, with reverence and respect, as do their descendants today. Tribal people deployed “TEK” (traditional ecological knowledge) to sustainably manage and harvest patches of wild plants for food, medicine, and other cultural practices. Access to land for these purposes has been greatly curtailed, however, mostly by land privatization and development, but also by some conservation land managers’ well-intended, but perhaps unduly strict, prohibitions against foraging. This workshop will present an indigenous perspective on the land, and its gifts, and how we may give back in return. It will also cover at least a dozen species of native plants with food and/or medicinal values, and where such plants could be planted (or may already be found) on conserved lands. The workshop will also look at the feasibility of reopening land trust and other conserved lands to plant gathering and other traditional practices by Native Americans and others seeking to do so in a respectful way. Examples of Cultural Respect Agreements between land trusts and tribal groups will be shared.

Presenter:

Russ Cohen – Until his June, 2015 retirement, Russ Cohen’s “day job” was serving as the Rivers Advocate for the Massachusetts Department of Fish and Game’s Division of Ecological Restoration, where one of his areas of expertise was riparian vegetation. Now Russ has more time to pursue his passionate avocation: connecting to nature via his taste buds, and assisting others in doing the same. Russ is now playing the role of “Johnny Appleseed” for edible native species. He has a nursery where he grows/keeps over 1,000 plants propagated from seed (some he collected himself), as well as obtained from other sources, such as the Native Plant Trust. He is then partnering with land trusts, cities and towns, schools and colleges, state/federal agencies, organic farms, tribal groups and others to plant plants from his nursery in appropriate places on their properties. Russ has initiated over two dozen such projects in the past five years.

Excellent stuff!