Erigenia bulbosa is a charming little plant. It is one of the earliest blooming wildflowers in the eastern United States, lending the common name Harbinger-of-Spring. The name Erigenia means “early born.” Depending on the climate, the tiny flowers of harbinger-of-spring may be found emerging above the leaves in woodlands as early as late January, though typically in February or early March. Harbinger-of-spring is dormant by April or early May, and all traces of the plant aboveground are gone, making Erigenia a truly ephemeral plant.

Harbinger-of-spring is a geophyte found most commonly on the west side of the Appalachian mountains, from New York to Georgia, and westward into eastern Kansas and Oklahoma. It seems to be especially abundant in calcareous areas where there is limestone bedrock and neutral or alkaline conditions. But it is by no means confined to such areas, and can thrive anywhere there is rich, well-drained soil as found in deciduous woodlands. Erigenia bulbosa appears to prefer mesic or moist conditions, such as floodplains along creeks and rivers, bottomlands, and Appalachian cove forests.

Erigenia bulbosa is in the parsley family, Apiaceae. The flowers are umbels, spreading open like an umbrella, with the stalks radiating from a central point. The red anthers on top of the stamens, later fading to black, make for a lovely contrast above the symmetrical white flowers. Another name for Erigenia bulbosa is pepper-and-salt describing the faded black anthers over the white flowers.

The parsley family – Apiaceae – is known for its umbels of perfect flowers. Perfect flowers are those which have both pollen-producing anthers, and pistils which contain the ovaries. Thus the flowers are hermaphroditic, being both male and female. As a consequence, they can be quite promiscuous to the point where sometimes a flower even pollinates itself, or a nearby flower on the same plant.

Another characteristic of the Apiaceae family is “sheathing” at the points where the leaf stems are attached to the main stalk of the plant. In botanical lingo this is referred to as petiolate. This sheathing can be observed in the pictures below.

The sheathing even protects the flowers of Erigenia bulbosa as they develop below the ground and facilitates their later emergence above ground. This delivery mechanism enables harbinger-of-spring and other parsley family members to send up their flowers first before any leaves. First come the flowers, then the leaves.

The thin, delicate leaves taste rather like parsley and can be used in numerous culinary ways.

Among the many wonderful traits of this plant is it’s ability to form colonies, blanketing the forest floor in parsley leaves and salt-and-pepper flowers. In the last couple of weeks of growth after the flowers have been pollinated and have begun to form seed, the stems lengthen and begin to sprawl out in every direction. This ensures that when the seeds ripen and fall off, they will be several inches away from the parent plant. It’s this habit that enables harbinger-of-spring to so effectively act as a groundcover.

Each branch in the umbel forms about 2-6 fruits (which have the seeds) per umbellet. There is usually an equal amount of sepals as fruits, but not always. The fruits are schizocarps, which means that they split into two equal halves when ripe, called mericarps. Each fruit seen in the picture below is two seeds.

As the tips of the sepals, along with the rest of the foliage, begin to turn yellow and brown, the seeds are nearly ripe and will soon fall off the plant to the soil below. If the fruits have begun to turn slightly yellow and drop off the plant with gentle handling, they are mature enough for collection. This is the point when you’ll want to come through and begin collecting seed by hand. Once gathered, keep the seeds moist to ensure their viability when sowing. I store them in moist soil, like from the forest where I gathered.

In northwest Georgia in the spring of 2017, the first few seeds became fully ripe and began to drop around March 21st. I first saw Erigenia bulbosa emerging at the same location on February 4th, so it’s about 6-8 weeks from first flowering to seed.

Harbinger-of-spring also has a starchy, edible tuber. Though small, ranging in size from a lentil to a ping pong ball, the roots pack a lot of nutrition and quite the flavor. It is edible raw, or cooked if desired. If gathered before the leaves have emerged, the root is emerging out of its einter dormancy and the sugars are highly concentrated. It has a pronounced sweetness to it, and an underlying nutty flavor. If gathered later in the season during its vegetative phase, the sweet overtones subside somewhat and the flavor may be described simply as “starchy.”

It is unknown how old Erigenia bulbosa can get but it is clear that they grow slowly and can take years until they are matured. Such lengths of time are not uncommon when it comes to spring ephemeral wildflowers. Respect and caution needs to be exercised during harvest. The most regenerative way to harvest is to dig when the seeds have ripened and fallen of their own accord, using the withering foliage as your guide to finding the root.

Based on the habit and ecology of this species, the seed is most likely not tolerant of drying. However, I did find some dried seeds on the tops of the plants, and above the leaf litter before making their way to the damp soil below. I will do a trial with a small amount of dried seed to test for viability in 2018, and will report back then.

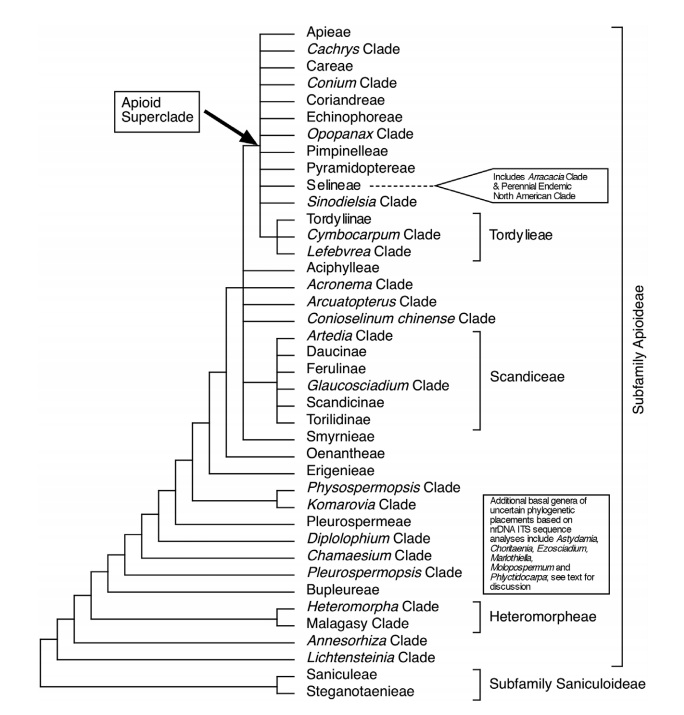

Now for an aside, and some taxonomical speculation. It appears to me that Erigenia bulbosa bears some striking resemblances with plants in the Selineae tribe of Apiaceae, showing closest physical similarities to the genus Lomatium and Orogenia. Common west of the Rocky Mountains, many Lomatium species, known as biscuitroots, are important indigenous foods of their regions. Like Erigenia, they are geophytes with starchy, nutritive tubers edible raw or cooked. Also like Erigenia, first the flowers appear, and then the leaves emerge later. And like Erigenia too, first the anthers are red, and then they fade to black. This characteristic lends the common name “salt and pepper” to both the biscuitroot and the harbinger-of-spring. I could go on with more similarities, but a picture is worth a thousand words.

The plants which bear the most similarity to Erigenia bulbosa are those in the genus Orogenia. Indeed, Orogenia was named in homage to Erigenia, and means “born of the mountains.” Emerging at almost the same time of year, with the same flowers, growing to the same height, Orogenia would be a dead-ringer for Erigenia if it weren’t for the differences in leaf shape and structure. Lomatium gormanii (known as sycan [see-chin] or chewaucan [shay-wah-kahn] to some Great Basin indigenous groups) is also strong look-alike.

Within the Apiaceae (parsley) family, the tribe which contains genus like Lomatium and Orogenia is the Selineae. Going by morphology alone, I would have placed Erigenia among them in the Selineae tribe too. Indeed, that is what many botanists have done in studies past. However, modern phylogenetic analysis reveals that Erigenia diverged at an earlier time than the Selineae, and places the genus as the solitary member of its own tribe, the Erigenieae (http://www.life.illinois.edu/downie/DownieITS.pdf). Just goes to show you that you can’t always go by morphological characteristics alone, at least not when it comes to taxonomy!

But outside of taxonomy, in terms of the the structure, habit, and gustatory qualities of Erigenia bulbosa, it could rightly be considered an eastern analog to the western biscuitroots.

I am lead to wonder whether Erigenia might cross with Orogenia or with Lomatium. And I wonder at what other potentials Erigenia might have in store.

Considering that Erigenia is a delectable geophyte that grows natively in deciduous woodland habitats, it is pretty exciting. I hope to be an advocate for more widespread planting of this attractive wildflower. While I encourage the gathering and sowing of native seed, it is worth pointing out that harbinger-of-spring does transplant successfully if done with care, or especially if done late in its season as the plant turns dormant. It is also available from a few select nurseries.

Well anyway, I sure do love this little plant, but that’s a wrap on this article I guess!

outstanding article with interesting conjecture, yeah

An excellent post, thanks. It sounds a little like our European Conopodium majus, but I find that isn’t palatable raw. Do you know of a seed supplier?

Do you have any seeds available of this species??

Hi Mark, all of my 2017 seed of this species has been sown. I should have more available by June 2018. Stay in touch around then! — Zach

When I saw the pictures I was thinking that is what we call Orogenia out west. The leaves are different, but in the field Orogenia never look like they should. Add to the (my) confusion I see that in late 2017 Orogenia has been reduced to synonyms of Lomatium.

Is there some place where we can purchase some of the seeds/bulbs so we can grow these?? Please let me know. They are so pretty!

Do you have any seeds available?

They are quite rare in Maryland. I would love to reintroduce it

Did you have any luck getting them to germinate?